- Article

- Comparative and Area Studies

Japan’s “Proactive Contribution to Peace”: A Mere Political Label?

June 19, 2014

The Fukushima nuclear accident turned Japan’s energy policy on its head, throwing into relief problem areas that had escaped scrutiny before the disaster. Electricity system reform is indispensable to rebuilding Japan’s energy policy and ensuring the success of Abenomics. This article by Research Fellow Hikaru Hiranuma was uploaded in September 2014 on the website of the Center for Asian Studies, Institut Français des Relations Internationales (Ifri), as part of its Asie.Visions series of electronic publications. It is reprinted here with Ifri's permission.

Executive Summary

The March 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station turned Japan’s energy policy on its head, shedding a harsh new light on Japan’s energy policy and power supply system, and throwing into relief six major problem areas that had largely escaped scrutiny before the disaster.

(1) Fragmentation of the power grid under the regional monopolies of Japan’s 10 “general electric utilities” and the resulting failure to develop the kind of wide-area transmission system needed to transfer electricity from regions with a surplus to those suffering shortages.

(2) The low electric supply capacity of entities other than the 10 regional utilities, making procurement of electric power from other sources difficult.

(3) The lack of effective mechanisms for curtailing demand at times when a reliable electric supply is jeopardized.

(4) The inability of customers to choose a power source or supplier.

(5) The failure to manage the energy risks associated with a shutdown of Japan’s nuclear power plants.

(6) The urgent need to confront the risk of severe accidents and other hazards associated with nuclear power facilities.

The pre-quake Strategic Energy Plan announced by the Democratic Party (DPJ) in 2010 put an emphasis on nuclear power as the mainstay of Japan’s energy supply and offered little guidance for addressing these issues. The plan was subsequently rejected, and a new policy was announced by the DPJ to eliminate nuclear power from Japan’s energy mix before 2040. The coalition agreement between the Liberal Democratic Party and the New Komeito Party, which defeated the DPJ in the December 2012 general election, backtracked from the “zero nuclear power” policy, which constituted an important shift from the nuclear-dependent policies of the pre- Fukushima era.

In April 2013, the LDP government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe approved a document titled Policy on Electricity System Reform emphasizing the need to make use of a wider range of energy sources, and in April this year, the cabinet adopted an updated Strategic Energy Plan aimed at reducing reliance on nuclear power as much as possible and building a flexible, diversified, multilevel supply-and-demand structure.

Many challenges remain to be overcome, however, such as accelerating the use of renewable energy, securing stable and lower- cost sources of fossil fuels, holding down rising electricity costs, and overcoming opposition to restarting nuclear power plants. Challenges related to the liberalization and unbundling of Japan’s power sector are also a lingering cause for concern.

The problems that emerged in the aftermath of 3/11 exposed the existing electricity system’s deep vulnerability. Sweeping reforms will be needed to overhaul this system and reduce reliance on nuclear power by diversifying energy sources.

Electricity system reform will thus be of vital importance. Such reforms will be advanced in a three-stage process under the April 2013 Policy on Electricity System Reform . However this scheme seems imperfect at best and a number of lingering concerns remain regarding its consistency and efficiency. Electricity system reform is indispensable to rebuilding Japan’s post-Fukushima energy policy and ensuring the success of the Abenomics program of economic growth. Japan must thus carry out drastic electricity system reforms, without being swayed by vested interests.

Introduction

The March 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station turned Japan’s energy policy on its head. The tragedy shed a harsh new light on Japan’s energy policy and power supply system, throwing into relief major problem areas that had largely escaped scrutiny before the disaster. Among them is the fragmentation of the power grid under the regional monopolies of Japan’s 10 “general electric utilities”; the difficulty to procure electric power from other sources; the lack of effective mechanisms for curtailing demand at difficult times; the inability of customers to choose a power source or supplier; the failure to manage the energy risks associated with a shutdown of Japan’s nuclear power plants and the urgent need to confront the risk of severe accidents and other hazards associated with nuclear power facilities.

The pre-quake Strategic Energy Plan, which was announced by the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government the previous year, with its emphasis on nuclear power as the mainstay of Japan’s energy supply, offered little guidance for addressing these issues. The plan was subsequently rejected, and a new policy was announced by the DPJ to eliminate nuclear power from Japan’s energy mix before 2040.

The coalition agreement between the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the New Komeito Party, which defeated the DPJ in the December 2012 general election, backtracked from the “zero nuclear power” policy, which constituted an important shift from the nuclear- dependent policies of the pre-Fukushima era.

In April 2013, the LDP government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe approved a document titled Policy on Electricity System Reform emphasizing the need to make use of a wider range of energy sources, and in April this year, the cabinet adopted an updated Strategic Energy Plan [1] aimed at reducing reliance on nuclear power as much as possible and building a flexible, diversified, multilevel supply-and-demand structure.

Many challenges remain to be overcome, however, such as accelerating the use of renewable energy, securing stable and lower- cost sources of fossil fuels, holding down rising electricity costs, and overcoming opposition to restarting nuclear power plants. Challenges related to the liberalization and unbundling of Japan’s power sector are also a lingering cause for concern. Sweeping reforms will be needed to overhaul this system and reduce reliance on nuclear power by diversifying energy sources.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is now advancing an economic policy called “Abenomics” aimed at lifting Japan out of the deflationary slump that had plagued the nation for more than 15 years and achieving sustained economic growth and fiscal consolidation. The Prime Minister sees the establishment of a new energy policy to promote technological innovation and create new markets[2] as key to spurring economic growth and enhancing Japan’s competitiveness. Electricity system reform will thus be of vital importance.

Japan’s Shifting Energy Strategy after 3/11

Fukushima and Japan’s Nuclear Energy Policy

The March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami in Tohoku and other parts of Japan triggered a serious accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station that developed into a full-blown crisis. The shocking images of explosions at the plant and white smoke rising from the reactor buildings are still fresh in people’s memories. Before 3/11, the safety of Japanese nuclear facilities had been almost an article of faith, as the government pursued an energy strategy centered on nuclear power. The Fukushima accident shattered the very foundations of Japan’s energy policy.

Less than a year before the accident, the cabinet had formally approved a national energy policy that sought to boost Japan’s dependence on nuclear power. The June 18, 2010, Strategic Energy Plan [3] —Japan’s primary energy-policy document—embraced the goal of expanding the share of electricity supplied by such zero-emission sources as nuclear energy and renewable energy from 34% in 2010 to 50% by 2020, and to 70% by 2030. The plan also envisioned construction of 9 new nuclear power plants by 2020 and at least 14 by 2030 with a view to increasing the contribution of nuclear energy to 50% from 28.6% in 2010.

Also on June 18, 2010, the cabinet approved the New Growth Strategy [4] drawn up by the National Policy Unit, an organ established under the Cabinet Secretariat soon after the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) took control in 2009. The New Growth Strategy was the DPJ government’s signature plan for ushering in a new era of growth—despite the constraints of a shrinking and aging population— by boosting international competitiveness and revitalizing Japan’s local economies, thereby ending the economic stagnation that had persisted since the collapse of the asset bubble in the early 1990s. With nuclear power staging a comeback in many parts of the world, the Japanese government not only stressed the need to secure stable supplies of uranium fuel to support nuclear energy but also called for the overseas expansion of the nation’s nuclear power industry as an integral element of its New Growth Strategy.

The Fukushima nuclear accident of 3/11 pulled the rug out from under these plans. In the summer of 2011, then Prime Minister Naoto Kan renounced the June 2010 energy plan and its vision of meeting 50% of Japan’s energy needs with nuclear power and pledged to go back to the drawing board on energy policy. The DPJ government of Kan’s successor, Yoshihiko Noda, embraced the goal of eliminating nuclear power from Japan’s energy mix before 2040—a policy incorporated in the DPJ’s 2012 general election manifesto.

The DPJ lost that election to the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its longtime ally the New Komeito Party (NKP), and the December 2012 coalition agreement between the LDP and the NKP rejected the DPJ’s “zero nuclear power” policy. Nonetheless, the two parties did pledge to “reduce reliance on nuclear power as much as possible through such means as energy conservation, accelerated adoption of renewable energy, and more efficient thermal power generation.” [5]

This in itself constituted an important shift from the nuclear-dependent policies of the pre–3/11 era.

Fault Lines Exposed by the 3/11 Disaster

In addition to shattering public confidence in the safety of nuclear energy, the Fukushima disaster had profound consequences for the regional and national economy. The shutdown of nuclear power facilities created the need for rolling blackouts and drove up the costs of fossil fuel imports [6] needed to make up the shortfall. The release of massive amounts of radioactive material forced the evacuation of tens of thousands of inhabitants, and a combination of misinformation and hysteria regarding radioactive contamination compounded the economic and emotional impact.

These dire circumstances shed a harsh new light on Japan’s energy policy and power supply system, throwing into relief six major problem areas that had largely escaped scrutiny before the disaster.

First, four issues emerged in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, even as the emergency continued to unfold.

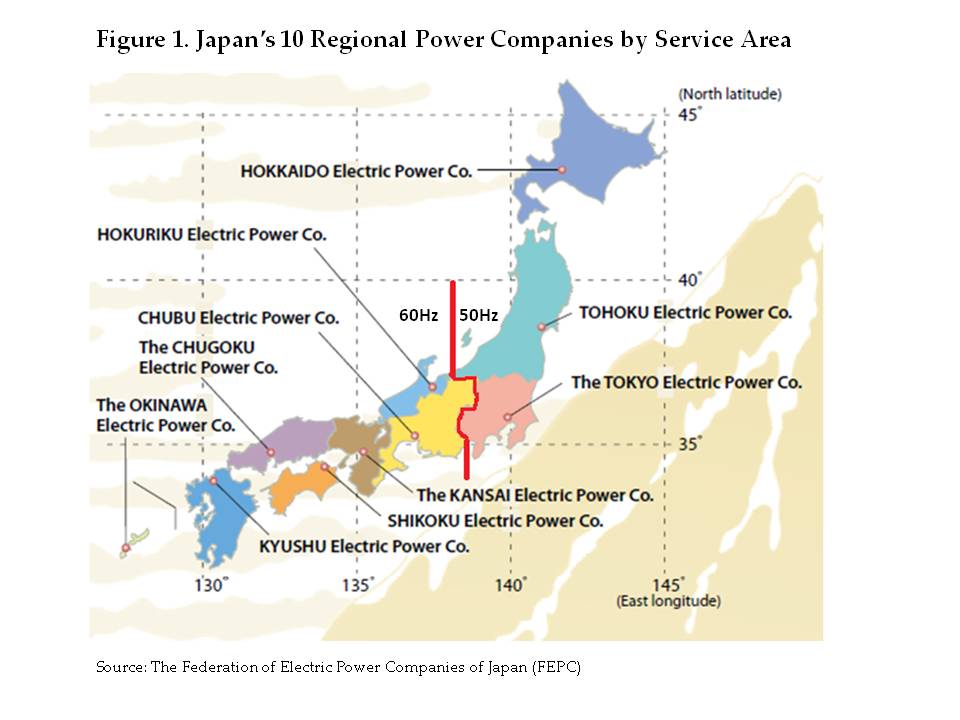

(1) Fragmentation of the power grid under the regional monopolies of Japan’s 10 “general electric utilities” and the resulting failure to develop the kind of wide-area transmission system needed to transfer electricity from regions with a surplus to those suffering shortages. (There are two incompatible transmission systems: a 50-hertz grid operating in the east and a 60 Hz grid in the west.)

(2) The low electric supply capacity of entities other than the 10 regional utilities, making procurement of electric power from other sources difficult.

(3) The lack of effective mechanisms for curtailing demand at times when a reliable electric supply is jeopardized (forcing Tokyo Electric Power to conduct rolling blackouts).

(4) The inability of customers to choose a power source or supplier.

As the full impact of the accident became apparent, two additional issues came to the fore.

(5) The failure to manage the energy risks associated with a shutdown of Japan’s nuclear power plants (interruption of power supply, rising fuel costs), notwithstanding Japan’s heavy dependence on nuclear power.

(6) The urgent need to confront the risk of severe accidents and other hazards associated with nuclear power facilities through rigorous emergency management, hazard mapping, evacuation plans, effective victim compensation programs covering damage from radiation scares as well as direct damage, and safe and effective disposal of radioactive waste.

The pre-3/11 Strategic Energy Plan, with its emphasis on nuclear power as the mainstay of Japan’s energy supply, offered little guidance for addressing these issues. After the Fukushima accident, the government set to work revising the plan, but the process proved to be contentious owing to sharp disagreements over the role of nuclear energy going forward—not only between the ruling and opposition parties but also within the LDP-NKP coalition. [7] It was not until this past April that an updated Strategic Energy Plan was finally adopted.

Electric Power Industry Reform Plan

Meanwhile, the LDP government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe faced the practical necessity of rebuilding the nation’s energy sector. In April 2013, the Abe cabinet approved a document titled Policy on Electricity System Reform , centering on the following three goals:

(1) Ensuring Stable Electric Power Supply

In view of Japan’s dramatically reduced reliance on nuclear energy since the Great East Japan Earthquake and its dependence on conventional thermal power generation [8] for most of its electricity needs, the policy emphasizes the need to make use of a wider range of energy sources, including distributed generation. It calls for a system that can ensure a stable, reliable power supply even while promoting expanded use of renewable energy, which is prone to fluctuations in power output.

(2) Keeping Electricity Rates as Low as Possible

The document pledges to keep electricity rates as low as possible, despite upward pressure on rates owing to the drop in nuclear power and rising fuel costs, by promoting competition, applying a nationwide merit order system (use of available energy sources in ascending order of marginal cost), and optimizing the capacity factor of power plants with the help of demand-response mechanisms that encourage voluntary reductions in peak demand.

(3) Expanding End-User Choice and Business Opportunities

The policy calls for a shift to a system that offers greater customer options, such as choice of power company, rate structure, and energy sources. It also pledges to build an electricity system receptive to innovation by opening the market to businesses from other industries and other regions and encouraging the use of new technologies for power production, demand response, etc.

For six decades, Japan’s electricity sector has remained essentially unchanged under 10 vertically integrated regional monopolies that control not only generation—mostly via large, centralized nuclear and thermal facilities—but also transmission, distribution, and sales. Throughout this time Japan has also endured the inconvenience of two incompatible transmission systems: a 50- hertz grid operating in the East and a 60 Hz grid in the West. The problems that emerged in aftermath of 3/11, as outlined above, exposed the system’s deep vulnerability. The April 2013 Policy on Electricity System Reform seeks to address these weaknesses in a three-stage process. [9]

The first stage entails the creation of an entity tentatively named the Organization for Cross-Regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, under the direction of the central government, for the purpose of balancing supply and demand on a nationwide basis and coordinating cross-regional transmission to deal with tight supply situations and power fluctuations accompanying the use of renewable energy. This body will have centralized access to all information pertaining to demand planning and grid planning, and it will be empowered to direct and coordinate cross-regional grid operation and transmission to adjust regional and interregional imbalances under normal and emergency conditions alike, while providing public access to neutral, unbiased system information. Stage two will completely liberalize the retail electricity market, opening it to competing businesses. And the third stage will separate the generation, transmission, and distribution sectors, using the legal unbundling approach, so as to ensure fair and neutral grid operation.

New Strategic Energy Plan

On April 11, 2014, approximately one year after approving the Policy on Electricity System Reform , the cabinet adopted an updated Strategic Energy Plan . It took the government more than three years to chart a new course for the nation’s energy policy following the devastating earthquake and nuclear disaster of 3/11.

The 2014 Strategic Energy Plan is built around two basic principles. The first confirms the “3E + S” thrust of Japanese energy policy, which emphasizes energy security while striving for greater economic efficiency and harmony with the environment , with safety as a basic premise. The second principle is “building a diversified, flexible, multilayered supply-and-demand structure.” [10]

What these principles amount to in policy terms is a complete overhaul of the status quo in Japan’s energy supply system, with its 10 regional monopolies, its vertical integration, its centralized generation by large power plants, and its east-west frequency disconnect.

Prior to the March 2011 disaster, the bulk of Japanese electricity came from either nuclear power stations or thermal plants fired by coal or liquefied natural gas. In 2010, nuclear power accounted for 28.6% of all electric power generated. Coal made up another 25% and LNG 29.3%. By contrast, oil-fired plants generated 7.5% of the total, large hydroelectric plants 8.5%, and renewable energy (excluding large hydro) just 1.1%. In 2012, following the Fukushima accident, nuclear power’s contribution plummeted to 1.7%. To cover the shortfall, Japan ramped up its dependence on coal, natural gas, and oil (see Figure 2).

One essential purpose of energy reform is to redefine the roles of thermal power (fossil fuels), nuclear power, and renewable energy in the nation’s energy supply system. This means determining the optimum energy mix going forward and elucidating the technical obstacles to be overcome in order to achieve that mix and maintain a smoothly functioning system.

Daunting Challenges to Reform

Inasmuch as Japan’s energy sector has functioned within the same framework for six decades now, it seems clear that meaningful reform faces a long and difficult road ahead. Indeed, serious obstacles have emerged even at this early stage. [11] This section will highlight some of the major issues confronting Japanese energy policy now and farther down the road.

Obstacles to Renewable Energy

The Fukushima accident exposed the vulnerability of an energy supply system built on centralized generation by a few large power plants and underscored the need for distributed generation using smaller, more widely dispersed power sources. This new awareness led to heightened interest in renewable energy as a means of fueling distributed generation while making effective use of local resources.

The Strategic Energy Plan acknowledges the importance of renewable energy as a “low-carbon domestic source of energy.” However, it offers no numerical targets for expanding the role of renewables in the energy mix, merely pledging to “pursue higher levels” than the targets previously adopted by the government— namely, 141.4 TWh, or 13.5% of all generated electricity, by 2020, as set forth in the “Outlook for Long-term Energy Supply and Demand (recalculated)” released by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry in August 2009; and 214.0 TWh, or roughly 20%, by 2030, as envisioned in the reference document “2030-nen no enerugi jukyu no sugata” (Shape of Energy Supply and Demand in 2030), prepared for a key meeting of the Advisory Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in June 2010.

As of 2012, the share of renewable energy (excluding large hydropower facilities) in Japan’s electric power output was still just 1.6%, and the obstacles to expansion remain daunting.

Currently, the government’s signature program for encouraging investment in renewable energy is the feed-in tariff (FIT) scheme launched in July 2012. Under this program, electric utilities are obligated to purchase electricity generated by government- certified renewable energy systems under long-term contracts, at a purchase price set by the government on the basis of generating costs.

Unfortunately, out of the thousands of systems that have been certified under the scheme, [12] only a small portion has actually begun supplying electricity. According to METI, as of the end of November 2013 the government had approved renewable energy systems with a combined capacity of 27,969 MW. [13] But the capacity of those systems that were up and running was only 6,453 MW. The remaining 21,516 MW worth of renewable energy systems are in limbo.

Why are so few of the FIT-approved renewable energy projects producing power? One theory has it that many of the investors who applied for approval had no intention of producing energy themselves. Under the program’s rules it was possible to secure approval for a system without owning, renting, or establishing superficies (above-ground rights) on the land needed to build or install such a system, provided one could produce a signed statement from the property holder. Moreover, the guaranteed purchase price was set at the time of approval, and there was no deadline for bringing the approved system online. Since the purchase prices were expected to go down over time, it seemed likely that investors were rushing to secure certification soon after the program’s launch with the sole aim of selling their certificates once purchase prices had fallen.

Whether or not investors actually intend to use their certification to produce electricity can be gauged to a large extent by their efforts to secure access to the necessary land and facilities. With this in mind, METI conducted a survey of the status of 4,699 solar PV generating projects with a capacity of at least 400 kW that had received approval during 2012. It found that, by capacity, only 8% of the approved projects had begun producing electricity. Another 22% had yet to secure either a site or generating facilities. However, most of the unrealized capacity consisted of projects that had already secured either property or facilities or both (see Figure 3).

This suggests that the program’s slow progress is not solely the fault of speculative investors who are sitting on their certificates as they await the best time to sell. The most likely reasons other than deliberate delay are:

- Funding delays

- Delays in procurement of land or materials (solar panels, etc.)

- Delays in connecting to grid (slow progress in arrangements with electric utilities)

- Delays in obtaining local development/construction permits, etc.

These are all issues that need to be addressed if Japan hopes to accelerate the shift to renewable energy. But the most troubling of these are delays in arranging a connection to the grid. Utilities routinely take four to six months simply to process a supplier’s request. Moreover, in Fukushima Prefecture, where expansion of renewable energy is urgently needed to aid recovery from the March 2011 nuclear accident, a multitude of problems have surfaced. It seems that the utilities have repeatedly refused to purchase renewable energy or have imposed stringent limits (citing exceptions in the law’s regulations), without providing clear-cut information on the maximum amount of renewable energy that can be purchased in any given part of the prefecture. The decisions made and the limitations imposed are arbitrary and unpredictable. [14]

If these issues had been addressed at the outset, a good portion of the 21,516 MW worth of renewable energy systems currently in limbo under Japan’s FIT scheme might already have begun supplying electric power to the nation.

In Japan, the FIT scheme is frequently highlighted as the country’s best hope for promoting greater investment in renewable energy. Yet it seems clear from the countless delays enumerated above that the program has done little to change an environment that is fundamentally hostile to the expansion of renewable energy. Incorporating distributed generation into Japan’s current centralized system is an uphill battle. To achieve real progress on renewable energy, we must move quickly to overhaul this centralized system and create an environment conducive to distributed generation.

Unresolved Nuclear Power Issues

Nuclear power policy in Japan has been a highly fraught issue ever since the March 2011 accident. Opinion remains sharply divided as to whether Japan should abandon its nuclear power plants altogether, retire them gradually, or invest in more.

In the midst of this raging controversy, the new Strategic Energy Plan identifies nuclear power as “an important baseload power source.” Baseload power is that component of the power production system that can be counted on to generate a constant, reliable supply of electricity day or night at relatively low cost. In short, the new Strategic Energy Plan assigns nuclear power a key role in Japan’s energy supply going forward. It also emphasizes safety as the “basic premise” of Japanese energy policy. Unfortunately, it leaves unresolved the critical issues that must be addressed to ensure the safety of nuclear power.

As of May 23, 2014, all of Japan’s nuclear reactors were offline, ostensibly awaiting maintenance or safety reviews. The technical safety reviews mandated in the wake of the Fukushima disaster are proceeding in accordance with the new regulatory standards adopted by the Nuclear Regulation Authority. But technical standards are not sufficient to guarantee nuclear safety. The government must also acknowledge the risk of accidents and establish policies and strategies to ensure the safety of local residents in the event of such a disaster.

The Fukushima disaster exposed the fiction of safe nuclear power and forced the country to acknowledge the risk of severe nuclear accidents. If anything has been learned from this tragedy, it is the need to prepare for the worst by drawing up hazard maps as the basis for concrete, practical evacuation plans (not academic exercises) and conducting meticulous evacuation drills in all high-risk areas. This is the task of disaster planning authorities at the local level.

As part of this process, officials in Shizuoka Prefecture, an area at high risk for a mega-quake, carried out a series of simulations to determine the best means of evacuating residents from the area around the Hamaoka Nuclear Power Station in the event of a nuclear accident triggered by a major natural disaster. The Shizuoka simulation concluded that if all residents within 31 kilometers of the facility attempted to evacuate by car at the same time, it would take 32 hours and 25 minutes for everyone to leave. Moreover, owing to traffic congestion, residents would be obliged to spend 30 hours and 45 minutes in their cars on average, increasing the risks of exposure to radioactivity.

The study concluded that in order to substantially reduce the time spent in transit, authorities would need to supervise the process closely to ensure that only about 3,000 cars departed each hour—all while providing necessary assistance to the elderly, infirm, and others in need of support and furnishing transportation for households without cars. This helps give some idea of the monumental challenge that local governments around the nation are facing in planning for a nuclear emergency.

Another important aspect of preparedness is a fair and workable system for compensating nuclear victims. Estimates of damages from the Fukushima nuclear accident continue to soar. In June 2013, the total was expected to reach more than 3.9 trillion ($38 billion). In January 2014, Tokyo Electric Power Co. (the plant’s operator) estimated the final bill at more than 4.9 trillion ($48 billion). No one is sure how all these claims will be paid for. Meanwhile, problems are brewing over the system of compensating residents according to their radiation exposure zone, with the highest payments going to those living in the “difficult-to-return area” (over 50 millisieverts annual exposure), lower payments to those in the “restricted residence area” (20–50 mSv), and the lowest to those in the “planned evacuation area,” (less than 20 mSv)—especially in cases where different zones exist side by side in a single community.

The new Strategic Energy Plan merely calls for an “overall review of the nuclear damage compensation system in the light of the energy policy set forth in this plan, including the role it assigns to nuclear power, and keeping in mind the situation surrounding the ongoing indemnification in Fukushima.” In view of the 140,000 Fukushima victims who continue to live as evacuees, reform of the compensation regime should be treated as a more urgent priority.

If the government intends to resume nuclear power operations,[15] it must, at the very least, secure the consent of the local community in advance, after providing full disclosure as to the kind of damage a nuclear accident can cause, how such damage occurs, the impact on inhabitants of the affected area, and how they would be compensated.

Another issue that needs to be addressed as quickly as possible is the disposal of spent nuclear fuel. The new Strategic Energy Plan pledges to address the problem of spent fuel head-on, rather than pass it on to future generations. But according to reference materials distributed at the 33rd session of the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee of METI’s Advisory Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in November 2012, only four of Japan’s nuclear power stations have the storage capacity for an additional 10 years worth of spent fuel, and even those with the greatest capacity will reach their limit in another 16 years.

Meanwhile, the government is no closer to securing a permanent disposal site than it was 14 years ago, when it enacted the 2000 Specified Radioactive Waste Final Disposal Act to ensure systematic and safe disposal of high-level radioactive waste from nuclear power reactors. Even supposing the government succeeds in getting the nation’s nuclear power plants online again, in the absence of a viable plan for solving this difficult problem, it will be obliged to shut them down again in the face of a nuclear disposal crisis—not in another generation or so but within the next 10 or 15 years.

To summarize, the proponents of nuclear power must grapple with four major challenges in the wake of 3/11:

(1) Ensuring the safety of Japan’s nuclear power facilities from a technical standpoint.

(2) Drawing up nuclear hazard maps and practical resident evacuation plans and conducting evacuation drills in the surrounding areas.

(3) Creating a workable system for compensating victims of nuclear accidents and securing the consent of local residents.

(4) Disposing of spent nuclear fuel.

Each of these challenges must be met if nuclear power is to play the role of an “important baseload power source,” as envisioned in the new Strategic Energy Plan. None of these will be easy to accomplish. But to kick the can down the road and resume nuclear power operations before all four are addressed would be to build unacceptable risk into Japan’s nuclear power program and, by extension, into the nation’s energy policy as a whole.

Fossil Fuels: A Need to Diversify

With the nation’s nuclear reactors idle and widespread use of renewable energy still a distant goal, Japan is more reliant than ever on imported fossil fuels—particularly natural gas, which causes fewer greenhouse gas emissions than oil and can be procured from a wider range of sources.[16] In fiscal 2012, natural gas accounted for more than 40% of Japan’s electric power generation.[17] The new Strategic Energy Plan describes natural gas as playing “a central role in Japan’s middle-load power supply.” Middle-load power falls between baseload power and peak-load power in terms of cost and its capacity for flexible output to meet fluctuating demand.

Unfortunately, Japan pays a high premium for the natural gas it imports. According to the International Monetary Fund’s Primary Commodity Price data, Japan’s March 2014 LNG import price averaged $17.92/MMBtu. By contrast, US prices averaged $5.25/MMBtu and European prices $10.81/MMBtu.

Japan posted a record trade deficit of ¥11.5 trillion ($112 billion) in 2013 thanks to the recent surge in fossil-fuel imports. While building an energy policy heavily dependent on nuclear power, the government made almost no effort to manage the risk of surging fossil-fuel prices in the event of a shutdown of the country’s nuclear power plants.

One factor behind Japan’s disproportionately high fossil fuel costs may be the “total cost calculation” system used for setting electricity rates. Under this system, electricity rates are based on the utilities’ calculation of the total cost of providing customers with power, which includes dividends to investors under the heading of “business return”.[18] As a result, the power companies have little incentive to lower costs.

Henceforth, securing reliable supplies of natural gas at lower prices will be a top priority for Japan’s energy policy. To achieve this, Japan must not only diversify its supply sources but also explore new methods of procuring and importing natural gas.

At present, Japan buys natural gas primarily in the form of liquefied natural gas. Indeed, Japan is the world’s single biggest importer of LNG, accounting for 36.2% of global LNG imports in 2012. This position by rights should give Japan considerable bargaining power, allowing it to push for more flexible contracts and hold down procurement costs.

But to exercise this bargaining power as a major LNG importer, Japan needs to stimulate competition among exporters. This means diversifying its supply sources by expanding imports from countries like the United States, Canada, and Russia instead of continuing its excessive reliance on the Middle East, Malaysia, and Australia.

Japan also needs to start exploring new approaches to purchasing and importing natural gas. Joint procurement in partnership with other natural gas importers could boost Japan’s buying power. By diversifying its mode of supply to include pipeline transport, instead of restricting itself to LNG, Japan could gain greater flexibility in its procurement of natural gas. The Tokyo Foundation policy proposal on Rebuilding Japan’s Energy Policy incorporates recommendations for diversifying Japan’s natural gas supply by means of a pipeline linking Japan to Russia’s Sakhalin gas reserves.[19]

Japan needs to get serious about lowering the cost of thermal power generation, and to that end it must begin thinking outside the procurement box and develop new sources and modes of supply.

Understanding Japan’s High Electricity Rates

Energy is the lifeblood of industry, and energy costs have a huge impact on the nation’s business activity. This is why cost considerations must be an integral part of any plan to reform the nation’s energy sector. We can see this thinking at work in the government’s 2014 Strategic Energy Plan, with its emphasis on “economic efficiency” (one of the Es in the “3E + S” formula).

With energy costs rising as a result of the shutdown of Japan’s nuclear power plants, the “renewable energy power promotion surcharge” has come under scrutiny for the burden it imposes on electricity customers. This is a surcharge applied to customer rates under the government’s feed-in tariff program.

In fiscal 2014, the surcharge was set at ¥0.75/kWh (0.74 cents), adding an estimated ¥225 ($2.21) to the average household’s monthly electric bill. The concern is that, as the utilities purchase more and more energy under the FIT scheme, the surcharge will continue to climb, and the burden on customers will grow.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that the FIT surcharge is only one small component of electricity rates. Although not itemized on customers’ bills, one can be sure that the high import price of natural gas in Japan, discussed above, plays a role as well. To better appreciate the relative importance of the various factors that determine the retail price of electricity in Japan, it is necessary to break it down into its basic components.

Japan’s electricity rates are indeed high by international standards, but this disparity existed long before 3/11. According to an International Survey of Electricity Rates released by METI in fiscal 2012,[20] TEPCO’s average “key rate component” was ¥12.6/kWh, substantially higher than the corresponding component in most other countries surveyed, including France, Germany, Norway, Spain, South Korea, and the United States (see Figure 4). This was in 2010, when nuclear energy still supplied a large portion of Japan’s electricity needs. The key rate component is the part of the electricity rate that is left when one excludes taxes, surcharges, and transmission and distribution (or wheeling) charges, which are more difficult to compare owing to country-by-country differences in taxation and the power transmission system.

The major cost factors included in the key rate component are power production expenses (fuel, plant maintenance, and personnel expenses) and administrative expenses (including meter-reading costs).

Why is Japan’s key rate component higher than that in other countries? The METI report identifies two main culprits: fuel costs and plant maintenance. Let us examine these one at a time.

While high import prices for natural gas have emerged as an issue of special urgency since the Fukushima accident, Japan was importing fossil fuels at high prices long before 3/11. These high costs were naturally reflected in the electricity rates customers paid in 2010. The report calculates that fuel costs contributed ¥4.73/kWh (4.64 cents) to the key rate component in Japan in that year, significantly more than in other countries.[21]

Table 1: Contribution of Fuel Costs to Key Rate Component by Country

Unit: ¥/kWh

|

|

Japan |

US (CA) |

South Korea |

Italy |

Spain |

|

Fuel cost factor |

4.73 |

3.77 |

2.68 |

3.49 |

3.61 |

Source: Based on Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, “FY 2013 Dengen ritchi suishin chosei to jigyo (Shogaikoku ni okeru denki ryokin no jittai chosa).”

A major issue highlighted in the new Strategic Energy Plan is the national wealth flowing out of the country owing to Japan’s increased dependence on fossil fuels to make up for the loss of nuclear energy. But what the plan fails to acknowledge is that this situation is the upshot of a policy that belittled the risks of a nuclear shutdown, even while promoting excessive dependence on nuclear energy, and a failure to manage those risks through diversification of power sources and development of underutilized domestic resources. When the “unthinkable” accident occurred, Japan was left with no choice but to import fossil fuels at high prices. The important thing now is to grasp the root cause of Japan’s current dilemma and learn from past mistakes.

METI’s International Survey of Electricity Rates also found that a major factor in Japan’s relatively high key rate component was maintenance costs—that is, the expense of maintaining the generating facilities operated by the utilities. In 2010, maintenance costs amounted to ¥2,668/kW ($26.16) in Japan, as compared with ¥777/kWh ($7.62) in South Korea (see Table 2). Here again, a basic underlying reason for this disparity may be Japan’s “total cost calculation” method, which minimizes cost-cutting incentives by allowing utilities to build corporate profits, as well as operating costs, into their electricity rates.

Table 2: Contribution of Maintenance Costs (Generating Facilities) to Production Costs by Country

Unit: yen/kW

|

|

Japan |

US (CA) |

South Korea |

Italy |

Spain |

|

Maintenance cost factor |

2,668 |

343 |

777 |

1,970 |

2,018 |

Source: Based on Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, “FY 2013 Dengen ritchi suishin chosei to jigyo (Shogaikoku ni okeru denki ryokin no jittai chosa).”

In order to formulate effective policies to contain energy costs, it is essential to break down electricity rates into their cost components and identify the factors responsible for Japan’s current high rates. As part of this process, it is necessary to assess the cost- cutting efforts the utilities have undertaken thus far under the current system, with its regional monopolies, centralized generation, vertical integration, and rate setting by “total cost calculation.”

Japan will need to embark on an unprecedented reform of the nation’s energy supply system, including substantial efforts to connect renewable energy to the power grid. While there may be a need to lower the FIT surcharge, focusing narrowly on the surcharge as if it were solely responsible for Japan’s high rates will not lead to smart policy. Japan needs to weigh its options in the broader context of energy reform, with an accurate understanding of the relative importance of various cost factors in Japanese electricity rates, and identify the best ways to control costs without sacrificing other key policy goals.

Lingering Concerns: Liberalization and Unbundling of the Power Sector

The new Strategic Energy Plan also highlights the importance of boldly reforming the energy supply-demand structure to overcome the challenges raised by the March 2011 nuclear accident.

This, as mentioned above, means overhauling an electricity sector monopolized by 10 vertically integrated regional companies generating power mostly via large, centralized facilities.

To build a wide-area transmission system, for example, it will be necessary to break up the regional monopolies. Creating a framework to hold down peak demand will require the introduction of market principles, whereby prices rise when supply grows short. Liberalization would also encourage new renewable energy companies and power producers and suppliers (PPS) to join the market.[22] Freeing up the grid and allowing equal access will also be needed to boost supply from companies other than the 10 regional monopolies.

The April 2013 Policy on Electricity System Reform contains measures essential to achieving the goals of new Strategic Energy Plan, to be carried out in three stages, as follows:

- Stage 1: Set up an organization for the cross-regional coordination of transmission operators under the supervision of the national government to address shortages in the power supply and facilitate the introduction of renewable energy sources, which are prone to supply fluctuations. The organization will be charged with operating a national-level network, balancing supply and demand, and providing unbiased information by around 2015.

- Stage 2: Fully liberalize the retail electricity market by 2016.

- Stage 3: Between 2018 and 2020, legally unbundle the processes of generating, transmitting, and distributing electricity and ensure their respective neutrality.

While these steps are absolutely vital, will they be enough to achieve the desired results? A number of lingering concerns come to mind.

The first is that Stages 2 and 3 seem to be in reverse order. The chief purpose of liberalization (Stage 2) is to encourage PPS and other companies to enter the market, thereby introducing greater competition. The markets for high-voltage (6000V) and special high- voltage (20,000V) electricity used by factories and other industrial users have been liberalized since March 2000, and 60% of the total electricity market is now open.

As a result, more local governments are putting the rights to provide electricity up to tender. One PPS reportedly won a contract to supply the Tokyo metropolitan government with electricity at a rate 6% lower than TEPCO. Despite this, however, as of November 2013 the PPS share of the liberalized sectors was just 3.5% and a mere 2.2% of total electricity demand.[23]

There are a number of reasons why more newcomers have not entered the market so far. One of the most important is that the electricity grid remains the property of the 10 regional companies. Lacking their own distribution network, the PPS are forced to pay high fees and surcharges, preventing more from entering the market. This problem could probably have been avoided had generation been unbundled from transmission first, opening up the grid and establishing a level playing field in which all companies had equal access.

The only area of the retail market that remains closed is the low-voltage (100–200V) sector comprising private households and similar users. The plan calls for this sector to be opened up as part of Stage 2 reforms. But if this occurs before generation and transmission are separated, the PPS are again likely to be prevented from entering the market. There is lingering concern, therefore, that such liberalization will have little impact on the enhancing Japan’s energy picture.

There are also concerns about Stage 3, since the formula used will be what is known as “legal unbundling,” which involves simply turning the utilities’ transmission departments into holding companies. As long as the power generating and transmitting companies are linked by capital ties, the unbundling is unlikely to produce the kind of level playing field that would give all power producers equal and fair access to the grid.

Alternatives exist to the legal unbundling option that should result in great equality and neutrality, including ownership unbundling to eradicate capital ties and divest the electricity companies of their transmission departments altogether—and function unbundling, which allows the utilities to retain their transmission facilities but assigns other companies to operate and control the grid.

Conclusion: Electricity System Reform Crucial to the Success of Japan’s Post-Fukushima Energy Policy

Opening up the power grid through electricity system reform to separate the power generation and transmission functions should enable more renewable energy companies to connect to the grid and help boost the share of renewable sources in Japan’s energy mix. Such diversification can reduce the risks associated with an overdependence on nuclear power. Fairer access to the grid should boost the market share of new energy sources and increase the number of energy providers.

Once the Organization for Cross-Regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, being set up during stage one of electricity system reform, launches operations, it will be possible to address shortages in the power supply on a cross-regional basis, facilitating the introduction of renewable energy sources that are prone to weather-induced supply fluctuations.

If the unbundling of electricity generation and transmission is accompanied by liberalization of the retail market, new power providers can be expected to enter the market, promoting competition and lowering prices.

There is good evidence suggesting that opening up the retail market does drive prices down. Increasing numbers of local governments are inviting companies to bid for the right to provide electricity, and in one such case, the price paid by the Tokyo metropolitan government to the winning contractor is now reportedly 6% cheaper than that charged by TEPCO. TEPCO itself established a new energy provider in May 2014 in preparation for market liberalization to sell electricity throughout the country—beyond TEPCO’s traditional area of operations—with the aim of keeping energy costs to a minimum and developing a competitive business.[24]

Greater competition in a more open market will incentivize electricity companies to procure fuel more cheaply and hold down rising costs for fossil fuels since the Fukushima accident. For example, the Chubu Electric Power Company reduced fuel costs by ¥35 billion in fiscal 2011, ¥15 billion in fiscal 2012, and ¥17 billion in fiscal 2013 (projection as of October 9, 2013).[25] Chubu Electric also signed a joint-purchase contract with the Korea Gas Corporation (KOGAS), the world’s largest purchaser of liquid natural gas, to acquire LNG from the Italian energy company ENI. The contract is running for five years, from May 2013 to December 2017. Liberalization of the market should provide additional incentives for electricity companies to reduce costs. At the same time it should encourage the diversification of fuel sources and the methods by which the fuel is acquired. This should have a positive effect on Japan’s energy security.

Advancing electricity system reform in these ways will contribute to the achievement of the goals of Abenomics through the development of innovative renewable energy technologies and high- efficiency thermal-fuel technologies, the emergence of new energy providers and renewable energy companies, and the creation of new domestic energy markets to support them. This will have the potential boosting economic growth and the competitiveness of Japanese industry. But this will happen only if the reforms are successfully implemented.

Whether Japan’s post-Fukushima energy policy can be successfully rebuilt and whether the Abenomics strategy for growth can produce hoped-for results therefore depend on replacing the system that had been in place for decades with a new, flexible, and innovative system in tune with current realities.

[1] The plan sets the direction for specific policy measures, so it is a key document on which Japan’s nuclear energy policy will be based. Enerugi kihon keikaku (Strategic Energy Plan), Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan. In Japanese: <www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/140411.pdf>. English translation (provisional): <www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/ 4th_strategic_energy_plan.pdf> (accessed August 28, 2014).

[2] The domestic market for clean energy is anticipated to grow under “Abenomics” from the current ¥4 trillion to ¥11 trillion by 2030 and that the global market will grow from ¥40 trillion to ¥160 trillion over the same period—making it on a par with the auto market.

[3] Enerugi kihon keikaku [The Strategic Energy Plan of Japan], Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan, June 2010.

[4] Shin seicho senryaku [New Growth Strategy], Prime Minister’s Office, Japan. In Japanese: <www.kantei.go.jp/jp/sinseichousenryaku/sinseichou01.pdf>. English translation (provisional): <www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/economy/growth/report 20100618.pdf>.

[5] <www.komei.or.jp/news/detail/20121226_9916> (Japanese only. Accessed August 28, 2014).

[6] According to the April 2014 Strategic Energy Plan, the shutdown of nuclear power plants since the Great East Japan Earthquake caused import fuel costs to rise by about ¥3.6 trillion in fiscal 2013, compared to the fiscal 2008–10 average.

[7] Diet members from both the ruling and opposition parties formed a group called Genpatsu Zero no Kai (Group for Zero Nuclear Power) in March 2012, and former Prime Ministers Jun’ichiro Koizumi and Morihiro Hosakawa established the Japan Assembly for Nuclear Free Renewable Energy in May 2014. At the same time, a number of LDP Diet members created a pro-nuclear group promoting the stable supply of electric power. As of January 24, the Genpatsu Zero no Kai had 64 members from nine (ruling and opposition) parties and both houses of the Diet.

[9] In the extraordinary session of the Diet in 2013, a bill to revise the Electricity Business Act was enacted. In the ordinary session of the Diet in 2014, a second revision of the act was submitted, and a third revision is planned to be submitted in in 2015.

[10] Strategic Energy Plan, METI, <www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/4th_strategic_energy_plan.pdf>.

[11] While the Strategic Energy Plan outlines the basic roles to be played by fossil fuels, renewable energy, and nuclear energy in meeting Japan’s energy needs, it fails to provide specific targets for the optimum energy mix owing to many unresolved issues.

[12] The FIT scheme targets the following renewable energy sources: solar PV (10kW or more, less than 10kW), wind (20kW or more, less than 20kW, offshore wind), geothermal (15,000kW or more, less than 15,000kW), hydroelectric (between 1,000kW and 30,000kW, between 200kW and 1,000kW, less than 200kW), small and medium-sized hydraulic (between 1,000kW and 30,000kW, between 200kW and 1,000kW, less than 200kW), biomass (biogas, wood-fired using forest thinned timber, wood-fired using other materials, waste, wood-fired using recycled wood)

[13] Japan’s total generating capacity in fiscal 2009 was 203,970MW. Incidentally, the capacity of Tohoku Electric Power, which supplies electricity to the Tohoku region, including Fukushima Prefecture, was 16,550MW, so in terms of capacity, renewable energy is already capable of supplying more electricity than Tohoku Electric. But it should be remembered that 93% of that capacity is solar PV, only around 13% of whose facilities are in operation.

[14] Comments made by panelists from Fukushima Prefecture at a Tokyo Foundation Symposium on “Fukushima’s Renewable Energy Initiatives,” September 12, 2013.

[15] The Nuclear Regulation Authority, during its regular meeting on July 16, 2014, acknowledged that Reactors 1 and 2 of the Sendai Nuclear Power Plant, operated by Kyushu Electric Power, were in compliance with new regulatory standards. NRA Chairman Shun’ichi Tanaka commented, however, that the NRA merely certified compliance with regulatory standards and did not claim that the reactors were safe. Detailed plans for safety measures must be submitted to and approved by the NRA before the Sendai plant can be restarted, so the plant is not expected to resume operations before this winter. Local residents have pointed out that satisfactory evacuation plans are incomplete, so gaining the approval of local residents could present a formidable challenge. Reported, for example, in “Genpatsu saikado o tou (6): Chiji tosshin, kaeriminu 30 kiro-ken,” Asahi Shimbun, July 23, 2014, and “Genpatsu saikado: Kuni ga handan o, Sendai tekigo-go, chiji ga hatsu genkyu,” Mainichi Shimbun, August 6, 2014.

[16] Japan imports all its natural gas in the form of LNG. Main suppliers in 2013 were the Middle East (29.2%), Australia (20.4%), Malaysia (17.1%), and Russia (9.8%), with the remaining 23.5% coming from other sources. Starting in 2017, Japan is slated to receive shipments from three US projects: Cove Point LNG, Cameron LNG, and Freeport LNG. For oil, Japan is reliant on the Middle East for 83% of its supply.

[18] “Business return” is generally around 3% of total investment, including that for existing plant and equipment, assets under construction, nuclear fuel, and operating capital.

[19] <https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=474>

[20] Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, “FY 2013 Dengen ritchi suishin chosei to jigyo (Shogaikoku ni okeru denki ryokin no jittai chosa)” (FY 2013 Power Source Site Selection Adjustment Project: International Survey of Electricity Rates), <www.meti.go.jp/meti_lib/report/2012fy/E002274.pdf>.

[21] While a simple comparison is difficult owing to differences in whether a country supplies its own fossil fuels or imports them and whether it gets its gas through a pipeline or as LNG, Japan still has higher costs than, say, South Korea, which otherwise faces a similar energy supply situation.

[22] The term “power producer and supplier” refers to electricity companies other than the 10 regional utilities, participating as new players in the liberalized retail energy market. They produce and supply electricity to users with contract electricity demand of 50kW or more via the grid managed and maintained by the utilities.

[23] Denryoku kouri shijo no jiyuka ni tsuite [On the Liberalization of the Electricity Retail Market], Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, October 2013.

[24] TEPCO press release, May 22, 2014.

[25] According to figures released by Chubu Electric on October 29, 2013. <www.chuden.co.jp/ryokin/onegai/houjin/hou_naiyou1029/hou_gaiyou/>.

The centerpiece of Japan’s first National Security Strategy , announced in December 2013, was a pledge to make a more proactive contribution to international peace. In an article reprinted from the May/June 2014 issue of Economy, Culture & History JAPAN SPOTLIGHT Bimonthly , Senior Fellow Akiko Fukushima places the concept in historical context, noting that it is a natural response to a transformed security environment and an extension of the security and international cooperation policies Japan has already been implementing in recent years.

* * *

On Dec. 17, 2013, the Japanese government announced its first-ever National Security Strategy (NSS) calling on the country to make a “proactive contribution to peace” based on international cooperation. The strategy has prompted questions from the media both at home and abroad about the strategy’s real intentions and its vision. Questions have been raised, in particular, about the phrase “proactive contribution to peace.” What does the phrase mean? Is it a mere political label? What sort of path will Japan embark upon under this banner, and is this a cover for Japan’s return to pre–World War II militarism and a rejection of postwar pacifism? This article will try to answer some of these questions.

Why Now?

Foreign scholars and policymakers have long criticized Japan for lacking a security strategy and, for that matter, strategic thinking in its security and foreign policy, making Japanese policy unpredictable and unaccountable. Some have even argued that with the ongoing shift in the balance of power, Japan could disappear from the radar screen of international relations unless it shows where it stands with a clear strategy. The NSS is a response to such criticism.

Basic Policy on National Defense

Japan did announce a national defense policy—the Basic Policy on National Defense—on May 20, 1957, and this has guided Japan’s defense policy to date. But it is a very short statement of only half a page, stipulating that the “objective of national defense is to prevent direct and indirect aggression, but once invaded, to repel such aggression, and thereby to safeguard the independence and peace of Japan based on democracy.” The policy cites four specific policies to achieve this objective, namely (1) supporting the United Nations, (2) nurturing patriotism, (3) building up national defense capabilities necessary for self-defense, and (4) maintaining security relations with the United States until the UN becomes capable of maintaining international security.

After World War II, Japan adopted a policy of aligning its security and foreign policy with the position of the UN under the so-called UN-centered diplomacy. The UN did not function the way Japan anticipated due to the East-West divide of the Cold War, however, prompting the country to turn to its alliance with the US as the cornerstone of its security policy. Today, more than 50 years since the adoption of the Basic Policy on National Defense, Japan confronts new challenges and a vastly transformed security environment. Thus there is an urgent need to update its basic policy to adapt to the prevailing situation.

Changing Security Challenges

Over the past 50-plus years, challenges to Japanese security have evolved beyond the defense of territorial integrity. Security challenges have diversified to include terrorism, piracy, cyber attacks, energy resources, space, climate change, pandemics, failed states, international crime networks, and the illegal trafficking of arms and narcotics, to name just a few. These challenges, such as cyber attacks, are hard to predict. In a globalized world, moreover, Japan’s security has become indivisible from that of other countries. Terrorists from far-away failed states may target Japan, and Japanese nationals may become victims of attacks thousands of miles from home. For example, Japanese nationals were killed in Algeria in January 2013 when the plant where they were working was attacked by a group allegedly affiliated with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. This showed that peace and stability in countries as geographically distant as Algeria have an impact on Japan’s security. Needless to say, piracy in the Gulf of Aden, which is a vital shipping lane, also affects Japanese trade.

The indivisibility, unpredictability, and diversification of security threats demand a more sophisticated, comprehensive, and integrated response. A long-term strategy is required, rather than ad hoc approaches to individual incidents.

Worsening Security Environment around Japan

Secondly, the security environment in areas around Japan has changed dramatically. In Northeast Asia, there are countries with large-scale military forces, and those either already possessing nuclear weapons or continuing with nuclear development. Recently, one of Japan’s neighbors has been asserting its position in the East and South China Sea by rapidly expanding and intensifying its activities in the seas and airspace around Japan, including by intruding into Japan’s territorial waters and air space. As Military Balance 2014 observed, defense spending in East Asia has expanded rapidly against rising tensions in the region. The shares of the region’s increase in real defense outlays in 2013 were 46% for China, 5.7% for Japan, 5.2% for South Korea, and 40% for other countries—split roughly equally between Southeast Asia and South Asia.

The Japanese government must do all it can to deter any aggression in its neighborhood and make diplomatic efforts to enhance cooperation with its neighbors to prevent a crisis from occurring.

Avoiding Misunderstanding

In an age of complex and intertwined security challenges, many countries, such as the US (since 1987), Britain (since 2013), Australia (since 2013), and South Korea (since 2009), have announced respective national security strategies. This is probably because they feel the need to explain their long-term security strategies both at home and abroad to avoid misunderstanding. Given the changes in the security environment, it is essential for governments to explain in advance how they plan to maintain peace and stability and to protect their citizens, both during peacetime and in contingencies. Long-term security strategies must also be explained to other countries to avoid unfounded misunderstanding on specific policies and to promote bilateral as well as multilateral cooperation.

In an age in which the security strategy of one country will have a large bearing on that of others, and as security challenges become increasingly transnational, international and regional cooperation will be crucial in ensuring an effective response. Such are the factors that have prompted Japan, too, to announce its NSS.

What Is a “Proactive Contribution to Peace”?

Background

Japan has been criticized for not doing enough for international peace and security, even being accused of “free riding.” The question of whether it can participate in UN collective security activities has been left unanswered since Japan’s accession to the UN in 1957.

In his letter of application for UN membership, dated June 16, 1952, submitted to UN Secretary General Trygve Lie, Japanese Foreign Minister Katsuo Okazaki wrote: “I, . . . having been duly authorized by the Japanese Government, state that the Government of Japan hereby accepts the obligations contained in the Charter of the United Nations, and undertakes to honour them, by all means at its disposal, from the day when Japan becomes a Member of the United Nations.”

The unspoken meaning of this phrase “by all means at its disposal” was that Japan would fulfill its UN obligations so long as they did not violate the Japanese Constitution. The question that remained was the means Japan could actually use, for Article 9 of the Constitution stipulates that “aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

The question of whether or not “by all means at its disposal” was a demarcation of its obligations and whether or not Japan can send its Self-Defense Forces on UN missions has been debated in the Diet since then. Soon after its accession to the UN on July 30, 1958, Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld asked the Japanese government to send 10 SDF officers as military observers to reinforce the United Nations Observer Group in Lebanon. Although the mission was to monitor a ceasefire and did not involve combat, the Japanese government declined the UN request because the mission might involve activities that were outside of the scope of existing domestic laws, including the Self-Defense Forces Law.

During the 1990–91 Gulf War, when Japan was accused of not doing enough despite its very substantial monetary contributions, it was likened to a cash dispenser, disbursing cash in piecemeal fashion without working up much of a sweat. In response to such criticism, the Diet subsequently passed the International Peace Cooperation Law (the so-called PKO Law) stipulating five strict conditions under which the SDF could be dispatched. Three of the conditions—the existence of a ceasefire agreement, consent of the parties for deployment, and impartiality—are the same as the UN’s PKO principles. Japan added two more, namely, (1) should any of the above three conditions not be met, the government of Japan may withdraw its contingent, and (2) the use of weapons shall be limited to the minimum necessary to protect the lives of personnel. These stipulations were intended to make sure that the dispatch was not unconstitutional. Since the law came into force in 1992, Japan has sent SDF personnel to places such as Cambodia, the Golan Heights, and Timor-Leste. Japan is currently participating in a UN peace- building mission in South Sudan.

The current official interpretation of the Constitution is that “Japan has the right of collective self-defense, as stated in the UN Charter, but cannot exercise it.” This interpretation has constrained Japan’s security role so far. Nevertheless, over the years Japan has been contributing to international peace, security, and prosperity through other means, including development assistance, capacity building assistance, and disaster relief, in addition to peace-keeping and peace-building activities.

What Does “Proactive Contribution to Peace” Mean?

As a basic concept, the NSS calls for Japan’s proactive contribution to peace based on international cooperation. I wrote a policy recommendation on proactive contribution to peace over a decade ago in March 2001 in a National Institute for Research Advancement (NIRA) Research Report entitled, “Japan’s Proactive Peace and Security Strategies.” I translated the concept as “proactive peace and security strategies” rather than a “proactive contribution to peace.” In the report I argued that:

Looking toward the 21st century, we Japanese need to make efforts to establish our identities as “Japan living in the global village,” based on the recognition that the existence of Japan is inevitably linked with other parts of the world. Undeniably, Japan’s traditional peace and security strategies after the end of World War II in which we declared “not to become an aggressor,” “not to possess nuclear weapons” and “not to export weapons” have contributed to world peace in no small measure. However, in the future, it is desirable to develop “proactive peace and security strategies,” where “Japan will proactively do something for world peace,” rather than reactive peace and security strategies.

Thus I placed “proactive contribution to peace” on the other end of the spectrum from the reactive and passive pacifism of postwar Japan. After World War II, as I noted above, Japan was cautious in playing a security role while it reconstructed and developed its war-ravaged economy. Japan wanted to remove its militarist image and wanted to portray itself as a peace-loving nation. In its public diplomacy, Japan avoided any image of militarism, even to the extent of not introducing traditional Kabuki and Noh plays in which samurai are portrayed. Also, Japan did not promote Japanese language education overseas—normally an important element of cultural diplomacy—until the 1970s because Japan’s prewar language education was strongly linked to military expansionism. Instead, Japan turned to the tea ceremony and flower arrangement to transmit a peaceful image of the country.

In the postwar period, it was sufficient for Japan to avoid talk of security issues to demonstrate its peaceful stance. And other countries did not expect Japan to play a significant role in defense and security, either. Today, however, in the face of the broadening, increasingly transnational nature of security issues, Japan can no longer ensure its own peace by doing nothing unless told. The international community, likewise, cannot afford to have the world’s third-largest economic power remain passive and reactive on security issues. We need to become more proactive in securing peace both at home and abroad. The basic principle of promoting peace has not changed, but we need to be more proactive.

In 2009 the Japan Forum on International Relations published a report entitled “Positive Pacifism and the Future of the Japan-US Alliance” which in its Japanese edition used the same phrase I had earlier proposed but used a different phrase—“positive pacifism”—for its English translation.

These were the ideas that eventually gave rise to the concept of a “proactive contribution to peace.”

Proactive Contributions Thus Far

Without using the label, though, Japan has already been proactive in its contributions to peace. One such example is the dispatch of Japanese SDF personnel and civilians on UN peacekeeping and peace-building missions. In recent years, Japanese nationals have participated in and even led UN missions in Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and elsewhere and have also served as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

The unanswered questions about Japan’s participation in UN PKO missions still remain, however. When I was in South Sudan in July 2013, Hilde Johnson, the UN Special Representative of the Secretary General, complained to me that the SDF cannot be deployed to dangerous zones, while Koreans are dispatched to unstable areas such as Jonglei. She hastily added, however, that she appreciates the high discipline of the Japanese contingent. This question is currently being debated by the Advisory Council on the Collective Right to Self-Defense, and a decision should subsequently be made by the government.

The second example of Japan’s proactive contributions to peace is the efforts made to mainstream and seek the implementation of the notion of human security. Since the speech by Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi in December 1998 announcing assistance for people hit by the Asian monetary crisis, Japan has promoted the broadly interpreted notion of human security embracing both freedom from fear (in such manifestations as conflict, terrorism, landmines, small arms, and human trafficking) and freedom from want (including currency crises, natural disasters, environmental degradation, infectious diseases, and poverty).

Some UN member states interpret the notion narrowly, focusing on the freedom from fear, while others view the concept as more broadly encompassing freedom from want. There are some who oppose the notion altogether, moreover, worried that “human security” might be used as a pretext to interfere in the domestic affairs of other countries with coercive measures. Concern has particularly been voiced over the notion of “responsibility to protect” which allows intervention with force in the event of massive genocide or other extreme cases.

Japan has led the discussions on human security, seeking a convergence of the various interpretations and eradication of concerns. Japan has tried to mainstream it by having a paragraph on human security inserted in the 2005 Outcome Document—the first mention in an official General Assembly document—and subsequently through the adoption of a common understanding of human security in UN Resolution 66/290. The resolution interpreted human security as embracing the right of people to live in freedom and dignity, free from want—that is, poverty and despair—and freedom from fear.

Japan has also advanced human security through official development assistance (ODA) to fragile states. This is corroborated in the August 2003 revision of the ODA Charter, which states that development should be approached from “the perspective of human security,” toward which end the protection and empowerment of individuals are important. Then in February 2005, Japan’s Medium-Term Policy on Official Development Assistance identified human security as a pillar of the nation’s ODA policy. This underscores the need for a human-centered approach and empowerment of local people—a thrust that has been embraced by the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

The United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security (UNTFHS) is the main avenue through which Japan has promoted the concept of human security. The Japanese government has continued contributing to the fund, donating a total sum of 42.8 billion ($390 million), as of October 2013.

While initially the sole donor, Japan has persuaded other UN member states supporting the concept to contribute to the fund. In response, Slovenia has contributed $47,000 and Thailand $60,000 since 2007, and in 2010 Greece gave $150,000 and Mexico $5,000. As of October 2013, the UNTFHS has funded 210 projects in 85 countries.

Although the UNTFHS was initially regarded as just another aspect of Japanese ODA, the Advisory Board on Human Security revised its guidelines in January 2005 to mainstream projects that include a wider range of interconnected regions and areas and in which multiple international organizations and NGOs participate with the intention of integrating humanitarian and development assistance by strengthening people’s capacity and seamlessly implementing assistance in the transitional period between conflict and peace.

The Rapid Assessment of the United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security , published by Universalia in May 2013, reports that the human security approach at the project level has filled unaddressed areas; empowered stakeholders; is a valuable tool in promoting the three pillars of the United Nations—development, human rights, and peace and security—and overall has had a beneficial impact.

The third example of Japan’s proactive contributions, related to the second, as the Chart shows, is its ODA disbursements. While assistance was initially offered to other countries in Asia, it is now provided worldwide, including Africa, contributing to the stability of the region. Japan not only assists conflict-ridden countries but also their neighbors, which could be affected by an influx of refugees or terrorists from failed states. Security and development are closely inter-related. When security is unstable and conflicts recur, the fruits of development could be wiped out. When a region remains undeveloped after conflict, local residents will not be at peace and may be unable to build a resilient society. Despite criticisms of the securitization of development, there is a nexus between security and development.

Chart

ODA Disbursement by Major Donors

The NSS specifically mentions that “Japan has garnered high recognition by the international community, by its proactive contribution to global development in the world through utilizing ODA. Addressing development issues contributes to the enhancement of the global security environment and it is necessary for Japan to strengthen its efforts as a part of ‘Proactive Contribution to Peace’ based on the principle of international cooperation.”

The fourth example is that the Japanese Ministry of Defense since 2011 has been providing capacity building assistance to other Asian countries in nontraditional security areas, including training for humanitarian assistance/disaster relief; non-combatant evacuation operations; training of coast guards for piracy control; training in peacekeeping operations focusing on infrastructure; and defense medicine. Such training and assistance would allow countries to utilize their own resources in dealing with crisis situations and can also deepen cooperation between Japan and the recipient countries, contributing to regional stability. Japan is also collaborating with Australia and others in capacity building assistance.

Japan has thus already been making proactive contributions to peace, and it intends to do more in the years to come. Japan has not suddenly shifted from a reactive to a proactive approach with the Dec. 17, 2013, announcement of the NSS. The strategy also emphasizes contributions through international cooperation, as security challenges are becoming more transnational. It calls for collaboration with other countries in the region and in the international community in domains ranging from cyberspace and terrorism to maritime security.

Japan’s Role in Promoting Peace & Stability

Japan’s “proactive contribution to peace based on international cooperation” is therefore not a mere political label or a cover for militarization. The NSS will enable Japan to be more strategic in implementing its contributions. The revised National Defense Program Guidelines, announced on the same day, reflects this thrust.