Three Points of Note Concerning the Latest Health Expenditure Figures: Accurately and Promptly Compiling Government Statistics

November 14, 2024

R-2024-033E

Announcement of the Latest OECD Health Expenditure Figures

The OECD released the latest health expenditure figures in July 2024. Health expenditures not only include expenditures for treatment, it is also a macro-cost statistic that includes nursing care and preventive care and is commonly used in Japan as well. Health expenditure is a processed statistic that is estimated in accordance with standards referred to as a System of Health Accounts (SHA) established by the OECD and other organizations. Figures for Japan are prepared by the Institute for Health Economics and Policy (IHEP).

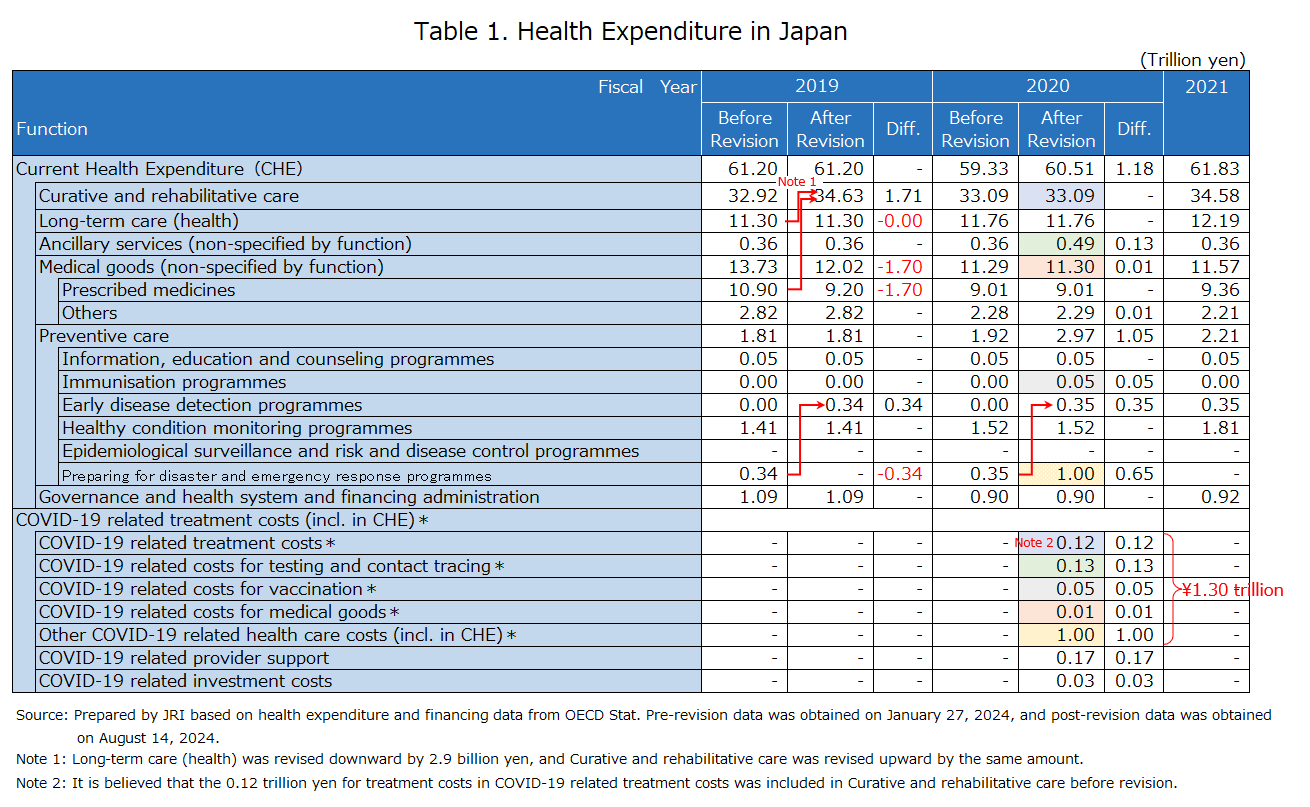

At this time, data for Japan from fiscal 2021 was released as the most recent figures, and revisions to data from prior years as well as information on COVID-19 related expenditures were also added. In recent years, there has been a growing awareness that the estimated figures of Japan’s health expenditures are not on a practical level,[1] and there are many points that should be kept in mind concerning the figures released at this time as well. Below, bold text is used for category names as appropriate to distinguish between general nouns and functional item names in the OECD statistics.

Fiscal 2019 prescribed medicines expenditures revised down sharply by 1.7 trillion yen

The first point of note is that prescribed medicines expenditures in fiscal 2019 were revised downward by 1.7 trillion yen (Table 1). In other words, it was confirmed that the figure for prescribed medicines expenditures in fiscal 2019 was vastly over-estimated. Health expenditures are broadly divided into current expenditure on health and gross capital formation, and of these, current health expenditure is categorized according to seven functions from curative care to government and health system and financing administration. It should be noted that figures for curative care and rehabilitation are aggregated for release.

Prescribed medicines are a major component of medical goods, and the pre-revision figure for fiscal 2019 was 10.9 trillion yen, but as a result of the recent adjustment, this figure was revised downward by 1.7 trillion yen to 9.2 trillion yen. The reduction amount of 1.7 trillion yen is equal to 0.3% points in comparison to GDP. Furthermore, the figure for curative and rehabilitative care was revised upward by nearly the same amount. In short, an error was made. Regarding the possibility that prescribed medicines were over-estimated, a colleague of the author pointed this out in a report released in May 2023 (Naruse (2023)), citing the 1.7 trillion yen figure. An inquiry was made to IHEP prior to the report’s publication, and the matter has finally been addressed.

Health expenditure data is widely used in key policy decisions, and this situation needs to be taken seriously. Most recently, health expenditure data was referenced in the fiscal 2024 medical fee revisions. Medical fees, which are the official prices for medical services, are broadly divided into medical service fees (core component) and drug prices. In the fiscal 2024 medical fee revisions, which were decided on December 20, 2023, the medical service fees (core component) were increased by 0.88%, while drug prices were reduced by 0.97%.

In the background to the decision to reduce drug prices was the perception that “Japan’s pharmaceutical expenditures as a percentage of GDP are extremely high among developed countries,” and the overestimate for fiscal 2019 prescribed medicines figures was one of the factors that contributed to the decision.[2] The pharmaceutical expenses, etc. referenced in “pharmaceutical expenses, etc. (as a percentage of GDP)” in the materials of the Fiscal System Council meeting held on November 1, 2023 refers to medical goods in current expenditure on health. Although the graph title indicates that the figures are for fiscal 2020, the data for Japan, which lags behind other countries in terms of timelines, is from fiscal 2019.

The circumstances under which the over-estimate was left unaddressed and used despite the possibility that it was an over-estimate being pointed out is unclear. The circumstances should be clarified to prevent recurrence, and pharmaceutical companies likely have a right to demand that the government adjust the drug price revisions.

New Doubts about Preventive Care, Which Always Had Numerous Problems

The second point is that a new and puzzling aspect has arisen concerning prevention, which has had many problems concerning estimates.[3] Regarding preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes, a sub-item of preventive care,[4] taking fiscal 2019 as an example, 0.34 trillion yen was reported before revision (Table 1). After revision, 0.34 trillion yen was transferred to early disease detection programmes (checkups). This was also the case in fiscal 2020. In fiscal 2021, preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes was set to zero, and early disease detection programmes (checkups) was 0.35 trillion yen.

Although somewhat late, the removal of figures that should not have been included under preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes is a positive development. Questions have previously been raised regarding the figures for preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes, suggesting that “these figures should be reported elsewhere” (Nishizawa (2020)). Even more puzzling, however, is that these amounts were transferred to early disease detection programmes (checkups) rather than immunization programmes.

Why should these amounts have been transferred to immunization programmes? The likely basis for this inference is technical, and consequently will not be discussed in this article (for details, see Nishizawa (2020)), but it is clear that the estimates were inappropriate from the fact that the figures for immunization programmes in fiscal 2019 and fiscal 2021 were nearly zero (Table 1). In Table 1, which expresses figures in units of 1 trillion yen, the figure for immunization programmes is 0.00 in both fiscal years, but in fiscal 2021, for example, the figure is 1.34 billion yen. Earlier years up to fiscal 2019 have similar amounts. For clarity, it should be noted that these figures are released as annual totals for all of Japan.

It is impossible, of course, that vaccinations in Japan cost only 1.34 billion yen annually. Local governments alone spend approximately 350 billion yen annually (excluding COVID-19) to provide regular vaccinations and subsidize voluntary vaccinations (such as Hib and pneumococcal vaccines). These figures can be obtained from Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications statistics.[5] It is not difficult to report the immunisation programmes category. Some corporate health insurance programs subsidize the cost of influenza vaccines for insureds, and if these costs were also included, the immunisation programmes category would likely be even larger.

Disclosure of COVID-19 Related Expenditure Items for Fiscal 2020

The third point of note concerns COVID-19 related expenditure items. This time, COVID-19 related expenditure items for fiscal 2020 were disclosed (Table 1). Among the COVID-19 related expenditure items, five items ranging from treatment to other (included in current expenditure on health) are figures that are included in current expenditure on health.

The current expenditures on health for fiscal 2020 were revised upward by 1.18 trillion yen from 59.33 trillion yen before revision to 60.51 after revision. The difference, equal to 1.18 trillion yen, is calculated by subtracting 0.12 trillion yen for treatment from the total of 1.30 trillion yen for the five COVID-19 related expenditure items. It is believed that the 0.12 trillion yen for treatment was already included in current health care expenditures before revision.

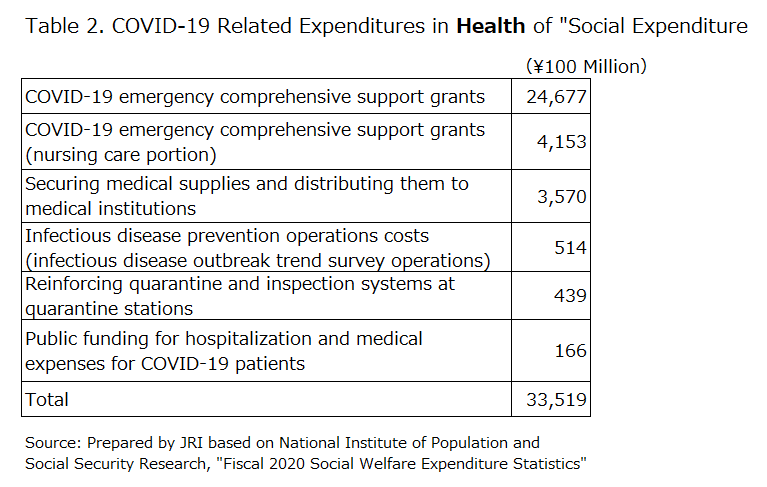

First is the scale of COVID-19 related expenditures, i.e., 1.3 trillion yen. When verifying the validity of these figures, it is effective to compare with the estimates prepared by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS). The IPSS estimates health expenditures as one policy area comprising social expenditures. Social expenditures along with social welfare benefit expenses are released annually as social welfare expense statistics. Health included in “social expenditures” is also estimated in accordance with SHA. Health expenditure includes not only public benefits, but also covers through household out-of-pocket expenses and private insurance, while social expenditures include only public benefits. Despite this difference, [6] both are estimated in accordance with SHA. Therefore, public benefits included in COVID-19 related expenditures, for example, should match health expenditure and the health portion of social expenditures.

However, COVID-19 related expenditures included in the health portion of social expenditures for fiscal 2020 was 3.3519 trillion yen (Table 2), a discrepancy of approximately 2 trillion yen from the 1.3 trillion yen in health expenditures referenced above. It is believed that the reason for this discrepancy is under-estimation of health expenditures.[7]

Second is the appropriateness of the categories where COVID-19 related expenditures are included in each function of total health expenditure. Within COVID-19 related expenditures, 1.0 trillion yen was categorized as other (included in current expenditure on health), and under current expenditure on health is included in preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes. It is believed, however, that most COVID-19 related expenditures should be included in the epidemiological surveillance and risk and disease control programmes category (see also Note 3). Epidemiological surveillance and risk and disease control programmes is the core function of public health centers. It is not possible that expenditure for epidemiological surveillance and risk and disease control programmes was zero, not only after the outbreak of COVID-19, but even before.

Third, it is believed that COVID-19 related expenditures were not included in current expenditure on health for fiscal 2021 (it is conjectured that these expenditures were included in treatment). As stated in the discussion of the first point of note, healthcare expenditures for fiscal 2020 were underestimated, even when considering only COVID-19 related expenditures, and it is believed that the scale of the under-estimation increased even further in fiscal 2021. As described above, the statement appearing at the beginning of this article that Japan’s health expenditures are not at practical levels is no exaggeration.

Shifting to Government-Compiled Health Expenditure Statistics

It was reported on July 19, 2024 that the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare will begin estimating healthcare expenditures in fiscal 2025 at the earliest (The Nikkei). “The policy of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare is to prepare new statistics that summarize and determine data for a wide range of medical services including vaccinations and checkups. Expenditures not covered by public health insurance will also be covered in accordance with international standard calculation methods. This will provide a more accurate understanding of the overall image of expenses relating to healthcare, and the information can be used when formulating social welfare policy. Calculations will start as early as fiscal 2025, and data will be released with existing statistical information. The new statistics will be compiled in accordance with what is generally known as ‘health expenditure.’” The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has not made any official announcement since this report, and it is crucial that reports are implemented accurately and promptly.

References

[1] Michinori Naruse (2023), “Points of Note Concerning OECD Pharmaceutical Expenditure Statistics,” Research Focus No. 2023-008

https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/report/researchfocus/pdf/14239.pdf

[2] Kazuhiko Nishizawa (2017), “Current Status of and Issues concerning Prevention Expense Estimates in Health Expenditure,” JRI Review Vol. 9, No. 48

https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/report/jrireview/pdf/9718.pdf

[3] Kazuhiko Nishizawa (2020), “Current Status of and Issues concerning Vaccination Expense Estimates,” JRI Review Vol. 5, No. 77

https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/report/jrireview/pdf/11527.pdf

[4] Kazuhiko Nishizawa (2022), “Development of Expense Statistics Relating to Prevention,” The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research Review, R-2022-018

https://www.tkfd.or.jp/research/detail.php?id=4014

[5] Kazuhiko Nishizawa (2024), “Current Status of and Issues concerning Expense Statistics Relating to Long-Term Care (LTC) Based on a Comparison with the Estimates in Social Welfare Expenditure Statistics,” Research Report No. 2024-005

https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/report/researchreport/pdf/15105.pdf

[6] Reiwa National Conference (2024), “Development of Business Operator Data and Health Care Statistics As a Basis for Medical and Nursing Care Policies”

https://www.reiwarincho.jp/news/2024/pdf/20240425_001_01.pdf

[1] For example, the Reinventing Infrastructure of Wisdom and Action (ReIWA) (2024) pointed out the following problem concerning Japan’s estimated healthcare expenditure figures, and requested that the government compile the statistics. “For example, in light of international standards, there are currently many items for which the covered scope is not appropriately set and for which figures are under-reported, such as drug costs and health and hygiene costs, but correcting this will enable international comparisons.”

[2] See the Ministry of Finance document titled “Social Welfare” p. 54 in the Fiscal System Council materials (November 1, 2023).

[3] For details, see Nishizawa (2022).

[4] A broad outline of sub items of preventive care can be organized as follows.

Information, education and counseling programmes: Home visits by public health nurses to pregnant and nursing mothers, mental health counseling, nutritional guidance, etc.

Immunisation programmes: Vaccination charges and healthcare institution outsourcing fees for rubella, BCG (tuberculosis), hepatitis B, rotavirus, Hib, pediatric pneumococcal vaccines, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, inactivated polio, measles, varicella, Japanese encephalitis, cervical cancer prevention, and influenza.

Early disease detection programmes (checkups): Early detection of specific diseases such as cancer screenings.

Healthy condition monitoring programmes (checkups): Regular health checks including vision and hearing tests, weight measurement, etc.

Epidemiological surveillance, risk and disease control: For example, the response to COVID-19 could include the operation of PCR test specimen collection centers, house calls of people receiving home care, the transport of infected people to hospitals, and the operation of oxygen stations.

Preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes: This item is believed to include the activities of Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMAT). A DMAT is defined as a medical team that has received specialized training and can mobilize quickly at disaster sites and accident scenes with large numbers of injured or ill persons. The team consists of doctors, nurses, other medical professionals, and administrative staff.

[5] According to "Expenditures Necessary for Social Welfare Programs" by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, expenditures necessary for vaccinations in the past three years were as follows (excluding COVID-19). Fiscal 2019: 307.5 billion yen; fiscal 2020: 353.9 billion yen; fiscal 2021: 321.1 billion yen. When estimating social welfare expense statistics, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research uses this "Expenditures Necessary for Social Welfare Programs" data.

[6] Expressed more precisely, health expenditures cover the following three items: (1) government and mandatory social insurance benefits, (2) household out-of-pocket expenses, and (3) voluntary health insurance. In contrast to this, only (1) is included in social expenditure.

[7] The estimate by the IPSS is superior to the estimate of the IHEP in terms of accuracy. Nishizawa (2024) compared the estimate accuracy of both with respect to LTC.