Human Capital Management as CSR — Beyond the Dichotomy of Responsibility and Strategy

February 7, 2025

C-2024-001-2WE

1.Introduction

Trends in business ethics are changing rapidly. CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility), CSV (Creating Shared Value), ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), SDGs (the Sustainable Development Goals), business and human rights, purpose, etc... Each time a new term or concept relating to sustainability appears on the scene, a variety of authors seek to describe its distinctions and relationships with other such concepts. Human capital management, the topic of this paper, has attracted significant attention in recent years as a key issue in the fields of business ethics and sustainability.

As the source of corporate competitive advantages shifts from tangible to intangible assets[1], the disclosure of human capital has been debated, initially in regions such as Europe and the United States. Japan has also seen a rapid rise in interest in the topic since the release of the “Ito Report for Human Capital Management” in 2020. This has led to the publication of numerous books elucidating human capital management, mirroring the growth in interest. Leaving aspects of human capital such as its definition and practical methods to these handbooks, this paper aims to answer the following question: “What is the difference between human capital management and the ‘consideration for people’ debated in the fields of business ethics and sustainability ?”

For example, imagine the following corporate statement on caring for employees. “We have always recognized employees as important stakeholders and endeavored to create work-friendly workplace environments as part of our CSR activities.” “At our company, we have pursued employee-friendly initiatives to address the “S” in our ESG.” “We promote the advancement of women as an initiative to contribute to achieving gender equality, the fifth SDG.” “At our company, we endeavor to prevent human rights violations in our supply chains in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. At the same time, within Japan, we strive to prevent harassment and discrimination and respect diversity.”

While all of these efforts could certainly be seen to concur with human capital management, however, it seems quite reasonable to suggest that the term “human capital management” itself is redundant. Is this really the case? One way to understand the meaning of a new concept or term is to explore its relationship with existing, related terms through comparison. For example, we can understand CSV through its differences and relationship with CSR; we can also understand what stakeholder capitalism means by understanding the philosophy of shareholder capitalism. Premised on such an approach, this paper interprets human capital management as one facet of a broader concept of CSR practices, comparing and examining its relationship with the existing concept of “labor CSR” to present one perspective on human capital management.

2.Reaffirming CSR

The starting point for this discussion is the reaffirmation of the basic CSR approach. The section below introduces the main definition of CSR, followed by an approximate summary of its implications.

(1) Definitions of CSR

To date, many researchers and institutions have attempted to define CSR. When discussing CSR from an academic standpoint, I should perhaps refer to the definitions suggested by academic researchers. In the context of corporate CSR practices, however, the definitions presented by international bodies seem to have become more widely known and accepted than those suggested in academic papers (Fig. 1).

The word “impact” is commonly used throughout these differing definitions and is a key term in understanding CSR. All business activities by corporations both great and small have two kinds of impact on society, to varying extents. One of these is “negative impact” and the other is “positive impact.” To say that companies fulfill their social responsibilities as members of society simply means that they accept responsibility for the impact that they cause. More specifically, they (1) reduce, as far as possible, the negative impact that may result from their business activities, and (2) they maximize their positive impact on society through their business activities.[2]

The former is often referred to as “passive CSR” and the latter as “active CSR.” Figure 2 presents a concise summary of their respective characteristics.

Figure 1: Main Definitions of CSR

|

Organization |

Definition of CSR |

|

EU (2011) |

CSR refers to “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society.” In other words, it means “maximizing the creation of shared value for their owners/shareholders and for their other stakeholders and society at large” and “identifying, preventing and mitigating their possible adverse impacts.” |

|

ISO (2011) |

Social responsibility is “the responsibility of an organization for the impact of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behavior.” |

|

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry |

CSR refers to “corporate behavior that takes responsibility for the impact of each company’s activities to enable it to coexist with society and the environment and achieve sustainable growth. It is an approach to corporate behavior that gains the trust of the various stakeholders of the company.”[3] |

Source: Prepared by the author based on materials published by each organization

It goes without saying that it is not sufficient to fulfill just one of these two responsibilities: companies are expected to fulfill their overall responsibility from the perspectives of both active and passive CSR. Even if the products a company delivers to the world boast excellent environmental performance, it cannot be said to satisfactorily fulfill its social responsibility unless it strives to reduce the greenhouse gases and waste emitted during the processes used to manufacture these products. Pursuing human capital management as part of CSR means simultaneously emphasizing both the active and passive aspects of CSR, as discussed later in this paper.

(2) Labor CSR

The term “labor CSR” came into use in Japan in the mid-2000s. One of the factors that led to the coining of this term — attaching “labor” to CSR — was the fact that the existing “Japanese-style CSR” approach was primarily concerned with external stakeholders: consideration for the environment, responding to consumers, strengthening compliance systems to prevent scandals, etc. (Iwade 2020, p.193; Inagami et al. ed. 2007, p.106). The term “labor CSR” came into use in this context based on a belief in the importance of positioning companies’ responsible treatment and consideration of employees — internal stakeholders — as a CSR issue.

To what, then, does labor CSR refer? Based on the understanding presented in this paper (Fig. 2), all CSR, whether environmental or labor, requires companies to address both positive and negative impacts. According to Iwade (2020, p.196), while labor CSR in Japan includes investment in human capital, its focus has been exclusively on compliance issues such as rectifying discrimination, respect for human rights, and ensuring safety and health; in other words, on practices to prevent negative impact. Interestingly, the same tendency can be observed in other countries. Brammer (2011) reviews previous cross-cutting research on human resource management theory and labor CSR to present their four most common themes: (1) Research into workplace discrimination and diversity (fair provision of opportunities); (2) Research into issues arising in global business (bribery and human rights issues such as child labor); (3) Research on health, occupational safety and health, and well-being; and (4) Research into the relationship between employee participation in CSR activities and well-being, etc. The author then proceeds to describe how three of these four themes deal with harmful aspects relating to labor (pp.301–302).

By contrast, the debate concerning human capital management is, if anything, more focused on how to achieve a positive impact. Seen through the CSR lens, labor CSR could be seen as passive CSR while human capital management could perhaps be characterized as active CSR due to the substantially strategic nature of the ideas associated with it. This paper, however, advocates against attributing the rise in interest in human capital management to the shift “from a narrow conception of responsibility to a strategic conception” or “from a passive to an active approach.” When Michael Porter proposed the concept of CSV, there was a trend in Japan to view it in terms of a transition “from CSR to CSV” or the idea that “CSR has been superseded.” However, it is not always appropriate to understand it in this way (Crane et al. 2014; Hartman and Werhane 2013). While the CSV approach itself is excellent, aiming to achieve a win-win situation between companies and stakeholders (society) from a strategic perspective, CSV does not replace CSR; rather, it should be understood as a part of CSR. CSV is a strategic and systematic characterization of the positive side of the impact described in the EU definition as “maximizing the creation of shared value for ... society at large” and in the ISO 26000 definition as “the impact ... on society and the environment.” Likewise, human capital management should not be perceived simply as a strategic tool; it is vital to be understood as a social responsibility. In other words, its understanding and practice should be premised on the dual nature of CSR, i.e. not only from the perspective of generating positive results but also in terms of preventing negative impact.

3.Human Capital Management as CSR

This section presents an examination of the significance of understanding human capital management as CSR based on the preceding discussion. Jumping straight to the conclusion, this paper makes the following three assertions: 1) companies should invest in human capital to fulfill their responsibilities in terms of both positive and negative impacts; 2) “risk avoidance” should not be understood in a narrow sense; and 3) companies should focus on the strategic link between “minimizing negative impact” and “maximizing positive impact.”

(1) Two facets of human capital investment

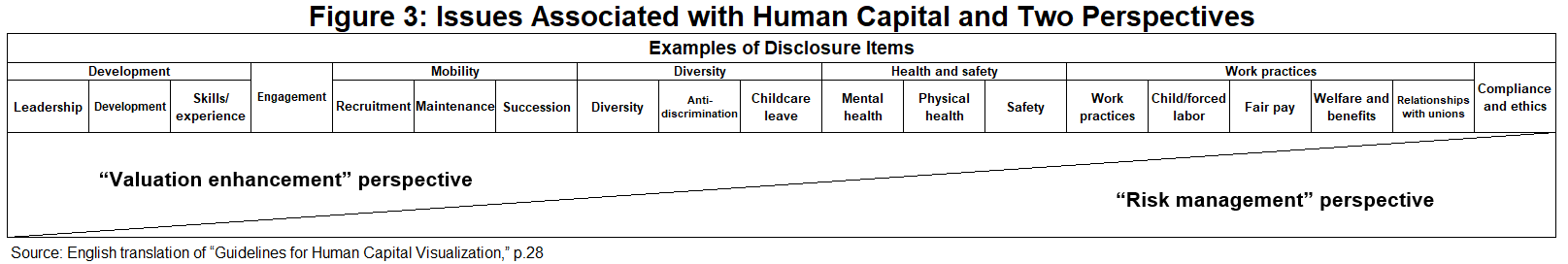

The “Guidelines for Human Capital Visualization” (hereinafter referred to as the “Visualization Guidelines”) announced by the Working Group on Non-financial Information Visualization of the Cabinet Secretariat in August 2022 summarize the various issues relating to human capital in terms of “value enhancement” and “risk” management (Fig. 3).

In this context, Japanese companies have engaged in labor CSR from the perspective of managing “risk,” but have been unable to generate substantial results from the perspective of “value enhancement.” Especially since the 1990s, after the collapse of Japan’s economic bubble, many Japanese companies have increased their employment of workers without regular employee status, whom companies do not necessarily have to develop as human resources. At the same time, they have perceived education and training for regular employees as “costs” and therefore reduced them (Yoshida and Iwamoto 2022, pp.30–31). Moreover, the lack of substantial increases in employee pay since the 2000s, despite ever-increasing dividends to shareholders (Itami 2024), also suggests that Japanese companies have perceived human resource management as a (reducible) cost. In this sense, human resource management goes one step further than the narrow interpretation of labor CSR that focuses on rectifying negative impacts. It can be understood as a movement to re-emphasize the importance of companies’ responsibility to generate positive impact. It should be stressed that positive and negative impacts are two halves of the whole: initiatives focused on one half do not exempt or offset companies’ responsibility to engage in initiatives on the other.

(2) How to interpret “risk avoidance”

The author advises caution, however, regarding what is meant by the risk management perspective in the Visualization Guidelines. The Visualization Guidelines explain this as the “perspective of avoiding a negative evaluation,” but this seems quite a limited characterization given the value standpoint of human capital management, which is premised on the importance of people. In other words, in terms of the subject of risk avoidance, the explanation in the Visualization Guidelines only presents risk avoidance from the corporate perspective.

The same limitation is evident in the way that the existing term “passive CSR” is understood. Passive CSR protects companies from scandals and prevents damage to corporate trust and corporate reputation. Here, too, the company is generally understood as the subject that should protect and be protected. When human capital management is seen in the context of CSR, however, the risk management required of companies is not limited to avoiding risk for themselves; rather, it incorporates the broader perspective of avoiding risk for all the people — employees, suppliers, and others — associated with the company. If human capital management positions employees and other people at the center of its approach, people should also be at the center of the strategies and risk management it advocates. The author agrees that the purposes of promoting human capital management include enhancing corporate value and avoiding corporate risk. However, this characterization of purpose — putting corporate interests at center-stage under the banner of strategy — has the potential of falling into a trap: it could be perceived as primarily focused on the interests of shareholders. While the results of the active promotion of human capital management by companies benefit employees and other people, companies risk the perception that this is nothing more than a means to maximize shareholder profits (Takeuchi 2023). The value of human capital will only increase in any genuine sense if companies invest in people, not to maximize shareholder profits but with the ultimate aim of caring for people.

(3) The strategic link between negative impact and positive impact

While the discussion above may seem to suggest that the assertions made by this paper are weighted toward consideration for negative impact, that is not necessarily the case. The final assertion concerns the possibility of linking the prevention of negative impact with the creation of positive results. It should be easy to imagine this possibility, even without the arguments presented in this paper. Imagine, for example, initiatives such as the abolition of discrimination, the elimination of factors hindering diversity, and the prevention of human rights violations, which would create better workplace environments and help to attract outstanding talent and improve productivity. There is no need to review such mechanisms here. Rather, this paper will end with a concise overview of the case of Unilever, which takes a more dynamic approach to understanding the link between negative and positive impact (Otsuka 2022).

Unilever upholds the purpose “to make sustainable living commonplace.” It has pursued business strategies in a way that does not sacrifice the interests of stakeholders. In terms of human rights, it published the world’s first “Human Rights report” in 2015 and has continued to update it since. One of the first sections in the 2020 edition of the Human Rights report carries the title “Our strategy,” together with the statement “Moving from ‘do no harm’ to ‘do good’” (Unilever 2020, pp.8–9).

Unilever identifies paying fair wages as one of its key issues for human rights. It has declared its commitment to “ensuring that everyone who directly provides goods and services to Unilever earns at least a living wage or income by 2030.” A living wage means a wage sufficient to maintain a satisfactory living standard, fulfilling basic household needs such as food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transportation, clothing, and preparation for unexpected circumstances. According to Unilever, enabling people to earn a living wage will support and help stimulate economic recovery in the local communities where it operates. “This in turn will fuel consumer demand and kickstart the engine of responsible and sustainable economic growth.” In the Visualization Guidelines, as well, wage equality is identified as a vital issue for avoiding a negative effect on reputation. However, Unilever perceives this from the perspective of value enhancement. In other words, Unilever sees suppliers not as “people who pose a risk to us if we don’t treat them appropriately” but rather as “people for whom we should have consideration based the values (purpose) we espouse” and “people who support our growth and that of society.” Its efforts to improve working environments are based on this understanding.

4.Conclusion

Looking back over the historical development of business ethics and CSR, there have been many cases where a specific, newly proposed concept or practice has been combined with a “strategic” perspective, and this together with strategy has become widely adopted: e.g. philanthropy has become strategic philanthropy, CSR has become strategic CSR, and passive governance has become active governance. In this sense, the recent debate on human capital management appears to the author, whose field is business ethics, to fall into much the same pattern: from labor CSR to strategic labor CSR. The strategic perspective facilitates both corporate and social sustainability and it will continue to be essential in terms of its ability to generate more value for society. At the same time, however, there remains a lingering fear that overemphasizing the strategic perspective will make it very easy to replace concepts such as responsibility and ethics with efficiency and productivity. Likewise, in the debate surrounding the SDGs, it feels as if companies’ responsibilities as social entities have been shelved amid the emphasis on linking SDGs to corporate strategy in recent years.

Human capital management is also often discussed using terms such as strategy, productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness. At the same time, however, it is vital that approaches to human capital management are also considered not as ways to facilitate strategy or gain a competitive advantage but as goals in themselves. If this is not achieved, then its necessity in an ethical sense will be forced into the background to make way for the logic that “initiatives that do not contribute to productivity are unnecessary.” This idea may seem like a mere idealism, but if we consider the past when CSR and compliance were also idealism, I think there is still room to consider how human capital management should be based on ethics.

[References]

Brammer, S. (2011), “Employment Relations and Corporate Social Responsibility,” Research Handbook on the Future of Work and Employment Relations, Edward Elgar, pp.296–318

Crane, A., G. Palazzo, L. J. Spence, and D. Matten (2014), “Contesting the Value of Creating Shared Value,” California Management Review 56, pp.130–153

European Commission (2011), “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Renewed EU strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility” pp.1–15

Hartman, L. P. and P. H. Werhane (2013), “Proposition: Shared Value as an Incomplete Mental Model,” Business Ethics Journal Review 1, pp.36–43

Unilever (2020), Human Rights report — Creating a fairer and more socially inclusive world, pp.1–98

World Economic Forum (2020), Human Capital as an Asset: An Accounting Framework to Reset the Value of Talent in the New World of Work, pp.1–35

Japan ISO/SR Committee (2011), ISO 26000:2010 — Guidance on social responsibility, Japanese Standards Association

Itami, Hiroyuki (2024), “Personnel Expenses and Capital Investments: Time to Increase Them,” The Nikkei, April 1, 2024, p.16

Inagami, Takeshi and JTUC Research Institute For Advancement Of Living Standards (ed.) (2007), Labor CSR — The Current Status and Issues in Labor-management Communication, NTT Publishing

Iwade, Hiroshi (2020), “Labor CSR Practices Aiming for ‘White Company’ Status,” Human Capital Management for Employee Satisfaction, Chuokeizai-sha, pp.191–205

Otsuka, Yuichi (2022), “Corporate Responsibility Relating to Business and Human Rights: What Kinds of Responsibility Does This Include?” Shujitsu Management Studies 7, pp.39–59

Takeuchi, Norihiko (2023), “Human Capital Management and Human Capital in the Sustainability Paradigm: Issues and Outlook from a Micro Perspective,” Organizational Science 57, pp.39–50

Working Group on Non-financial Information Visualization, Cabinet Secretariat (2022), “Guidelines for Human Capital Visualization,” pp.1–46

Yoshida, Hisashi and Takashi Iwamoto (2022), Human Capital Management to Achieve Corporate Value Creation, Nikkei Business Publications

[1] For example, “Human Capital as an Asset,” a report published by the World Economic Forum in 2020, explains that human capital, as an intangible asset, “can be a company’s greatest asset; it can make or break the business strategy and is a key differentiator” (World Economic Forum 2020, p.6).

[2] Proactive engagement in social contribution activities and philanthropy are also included in the scope of CSR, but these topics are beyond the purview of this paper. Although accountability for the systems put in place to fulfill these two responsibilities (minimizing negative impact and maximizing positive impact) and the results of their efforts are also included in CSR, this paper does not consider these matters in depth.

[3] “Value Creation Management, Disclosure/Dialogue, Corporate Accounting, and CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)” Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry website (Japanese only)

https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/economy/keiei_innovation/kigyoukaikei/index.html (August 13, 2024)