C-2024-001-3WE

1. Introduction

The past few years have seen a rapid advance in the debate on the regulation of sustainability-related disclosure. The period up to about 2028 has been characterized as the era of sustainability-related disclosure. The meaning and concept that define the term “CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)” have expanded beyond their previous interpretations in terms of management philosophy and social contribution activities to encompass a diverse range of subjects, including CSV (Creating Shared Value) and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance). Today, this movement is at last becoming integrated into capital markets.

Investment activities and management, too, have moved into a new phase with the advance of sustainability-related disclosure. Already, investors have begun to base their investment decisions on companies’ ESG information, in terms of their externalities and long-term risks. In corporate management, as well, there are attempts to clarify the relationship between ESG and corporate value, with managers recognizing hitherto unmeasured intangible assets and social impact as sources of their companies’ value creation.

“Human capital” has become a major focus in this context. In Japan, interest in human capital has risen since the 2018 publication of ISO 30414 (Human resource management — Guidelines for internal and external human capital reporting). “Investment in human resources” is one of the core themes of the “New Form of Capitalism” proposed by the Japanese government[1], and the Revised Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, published in 2021 in response to this proposition, also recognizes the importance of investment and disclosure relating to climate change and human capital[2].

At present, disclosure regulation has progressed in advance of companies’ ability to prove the value of human capital. In the future, however, the social accumulation of sustainability data will lead to an era when it is possible to interpret the trends and relationships between sustainability and corporate competitiveness, human capital and corporate revenue, company by company. For a perfectly competitive market, it is essential to eliminate information asymmetries. The disclosure of sustainability information, including information on human capital, will facilitate appropriate decision-making by diverse stakeholders, including investors and consumers.

2. Trends in Human Capital-related Disclosures

It was the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that took the lead in introducing the statutory disclosure of human capital. In 2020, the SEC revised Regulation S-K[3], mandating the disclosure of human capital by US-listed companies. The SEC adopted a principle-based approach, however, leading companies to disclose a wide variety of metrics. In 2023, the SEC’s Investor Advisory Committee recommended the disclosure of the following metrics (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Human Capital-related Metrics Recommended by the SEC Investor Advisory Committee

|

Main Human Capital-related Metrics for Disclosure |

|

The number of employees in each division and business, broken down by whether they are full-time, part-time, or contingent workers |

|

Number of years of continuous service and employee turnover rate |

|

Total amount of investment in human resources and compensation by employee attribute |

|

Diversity |

Source: Extract from SEC Investor Advisory Committee materials[4]

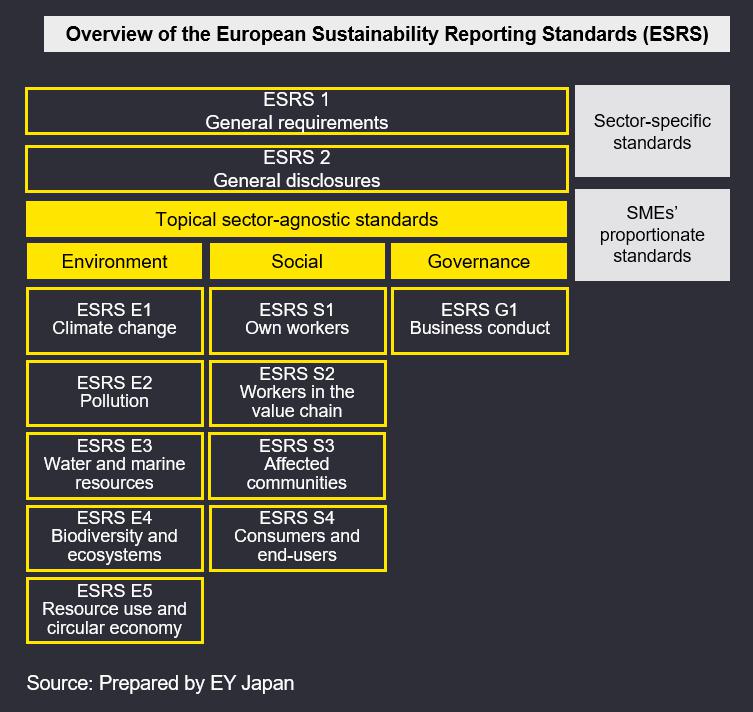

The European Union (EU) began the operation of its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in 2024. The CSRD mandates the disclosure of sustainability information designated under the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) for all large companies and listed companies in the EU, as well as companies outside the EU that derive a specific amount of their sales from the EU. The scope of companies subject to the CSRD will progressively increase until 2028, with even the headquarters of companies based outside the EU, but engaged in business activities within the EU, subject to its requirements.

The ESRS provides for the disclosure of a broad range of environmental, social, and governance sustainability information (Fig. 2). Unlike in the case of the SEC, it focuses on the disclosure of information on the externalities attributable to companies, targeted at a broad range of information users: stakeholders including civil society. From this standpoint, the information on human capital that it designates for disclosure also differs from that of the SEC, focusing on the rights of workers.

Figure 2: Elements of the ESRS in the CSRD

In Japan, the Disclosure Working Group of the Financial Services Agency’s Financial System Council indicated a direction for draft reforms of the Cabinet Office Ordinance on the Disclosure of Corporate Affairs, etc. in 2022 and the disclosure of human capital-related information in annual securities reports became mandatory in 2023.[5]

The main metrics for disclosure in the “Employees” section are the percentage of female managers, the childcare leave uptake rate among male employees, and the gender pay gap, based on the Act on the Promotion of Women’s Active Engagement in Professional Life and the Act on Childcare Leave, Caregiver Leave, and Other Measures for the Welfare of Workers Caring for Children or Other Family Members. It is expected that companies will include “governance,” “strategy,” “risk management,” and “metrics and targets” relating to human capital as part of their sustainability-related information, in line with the disclosure framework recommended by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) (Fig. 3). Such disclosure demonstrates an awareness of companies’ sustainable value-creation activities.

Figure 3: Human Capital-related Information Disclosure Expected in Japan

In this way, while some disclosure items are common to all the countries and regions, some differ, largely due to differences in the policymaking process[6] and policy principles. For example, Europe is pursuing the European Green Deal policy[7] and the approach to corporate disclosure corresponds with this policy. On the other hand, partly due to concerns that European companies, shunning such stringent regulations, will redirect their products (goods) and funds (money) away from the EU, European governments are also engaged in protecting domestic industries, establishing disclosure regulations that will present effective non-tariff barriers in their trade and capital policies. In the US, the source of corporate value is already shifting towards human capital and other forms of intangible value. The companies referred to as GAFA[8] are a leading example of this. For this reason, to assess the intrinsic value of companies, investors require information on its source: human capital. The policies adopted by Japan are thought to be the result of cherry-picking the best points from this international trend, taking account of Japan’s circumstances. With the domestic working-age population forecast to dwindle, increasing foreign investment in Japan and the further promotion of women’s social participation have been essential for the country’s sustainable growth going forward. At the same time, these two endeavors have been hampered by Japanese companies’ insular governance[9] and their old-fashioned employment practices and corporate culture, including the lifetime employment system and male-dominated work environments. It was therefore crucial to bring about a change in these characteristics. Meanwhile, there has already been substantial research into intellectual asset management and the disclosure of intellectual property, given the importance of technological assets to Japan as a resource-poor country. Therefore, in 2022, as human capital became a key focus of international debate after the release of ISO 30414, the administration of Prime Minister Kishida began to advocate its New Form of Capitalism, and the business community seized on this as an opportunity to further boost Japanese companies’ globalization efforts. At the same time, it advanced the debate from intellectual asset management to human capital management as a tool for restoring corporate value.

In this way, the background and aims of human capital disclosures differ by country and region. They are all statutory disclosures, however, requiring companies to gather information on human capital on a consolidated basis and disclose it in line with established standards. Behind these regulations and standards lie the interests and intentions of investors — the information users — as well as countries and regions. A passive response to these regulations and standards risks misinterpreting their real essence. Companies are expected to provide disclosure that more strategically, actively, and convincingly explains their intrinsic value.

3. Human Capital-related Information and How to Read It

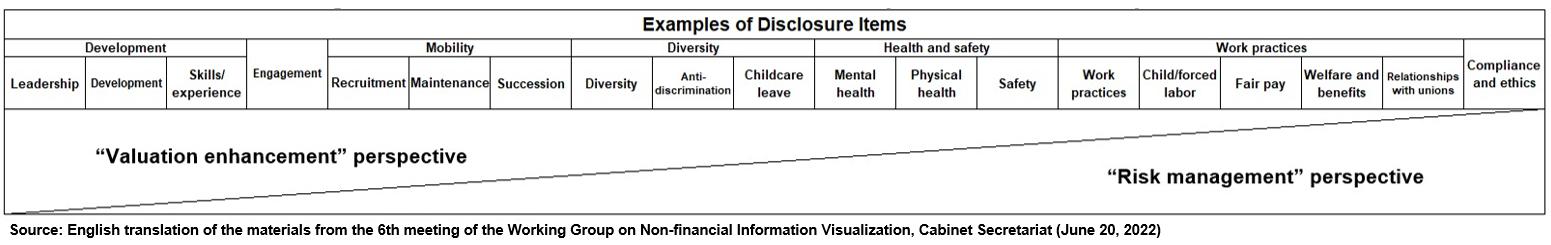

The objectives of human capital disclosure can be roughly categorized into “value enhancement” and “risk management.” (Fig. 4). Companies focusing on the former tend to disclose information related to human resources mobility, development, and incentives: how they attract and encourage outstanding talent. On the other hand, companies such as those with manufacturing bases in multiple countries disclose information related to matters including occupational safety and health and human rights. Obviously, it is important that companies maintain both perspectives and disclose the information appropriate to each context.

Figure 4: Conceptual Representation of the Levels of Human Capital-related Metrics (From the Perspectives of Valuation Enhancement and Risk)

Many of Japan’s manufacturing companies, apart from financial institutions, have grown from factories. Their human resources divisions are situated at each factory and business departments tend to be tasked primarily with labor management, such as handling workers and labor unions. Since the disclosure of consolidated financial results became common practice at the start of the 2000s[10], the accounting and finance divisions responsible for preparing financial reports have come to collect human resources data to meet the need for information such as the number of employees on a consolidated basis. Different countries have different work practices and labor laws, and the labor market environment differs for each business. Therefore, it has always been somewhat unreasonable to expect headquarters’ human resources divisions to collect human resources information on a global level. However, increasingly intense global competition over the past decade or so has led to more global companies strengthening their human resource (HR) functions to a global level in the belief that only companies that can select potential future leaders from within the group on a global scale will be competitive. In line with this movement, human resources divisions themselves have had to take on more sophisticated roles, shifting from labor management to HR strategy. It has also started to become necessary to integrate the management of human resources information throughout entire corporate groups.

The respective weightings of value enhancement and risk management within each company’s disclosure of human capital-related information differ depending on its management strategies, as do the positioning and management of human capital itself. For example, many companies have begun to disclose metrics relating to diversity. Laws such as the Act on Equal Opportunity and Treatment between Men and Women in Employment[11] have been established for the purpose of protecting the equal rights of men and women, with companies required to disclose metrics such as the proportion of women from a human rights perspective. Overseas as well, companies are disclosing similar kinds of information, with some even disclosing the proportions of each racial group. On the other hand, some companies are engaging in diversity as part of their strategies to attract talented individuals on a global level, across racial, gender, and national borders. Workplace environments that are accepting of diversity, such as these, can serve as a basis for innovation. In this way, while many companies may use the same diversity metrics, these metrics have a different strategic significance and background for each company. The different levels of strategic importance of metrics such as recruitment numbers and employee turnover rates between startups, which prioritize quantity and speed of recruitment to meet growth markets, and large mature companies, which replace or reskill their human resource portfolios in line with changes in the market environment, also make it essentially meaningless to compare these companies by numbers alone. It is vital to understand the strategic context that lies behind the numbers. Numbers have no meaning in themselves; rather, they represent the results as of a certain stage in the execution of strategies. What is important is for issuers to explain the connectivity between these numbers and their strategies. In recent years, HR information such as this has become useful not only for investors picking stocks but also for job seekers choosing potential employers in the labor market. It would be good if disclosure regulation spurred companies to appropriately ascertain the status of their own human resources and provided an opportunity for them to revise their management and HR strategies.

4. Integrating Human Capital-related Metrics with Finance and Accounting

While containing the word “capital,” the author has yet to hear any investor refer to human capital as a component of the capital on the balance sheet. It is often thought of as a component of assets: a kind of unowned intangible asset. Today, with the recent increase in labor force mobility and the existence of a labor market, it may be possible to place a valuation on human capital, if so desired, in terms of the potential market value of a company’s own human capital, were it bought or sold. The author himself has previously attempted such a valuation but was uncertain how to handle the resulting figure. If the value of a company’s human capital is high, it means that the company is employing personnel with a high intrinsic value at a discount, signifying a high risk of employee resignations. The reverse is also true: if a company pays a premium to employ personnel with a low market value, it may be incurring excessively high costs.

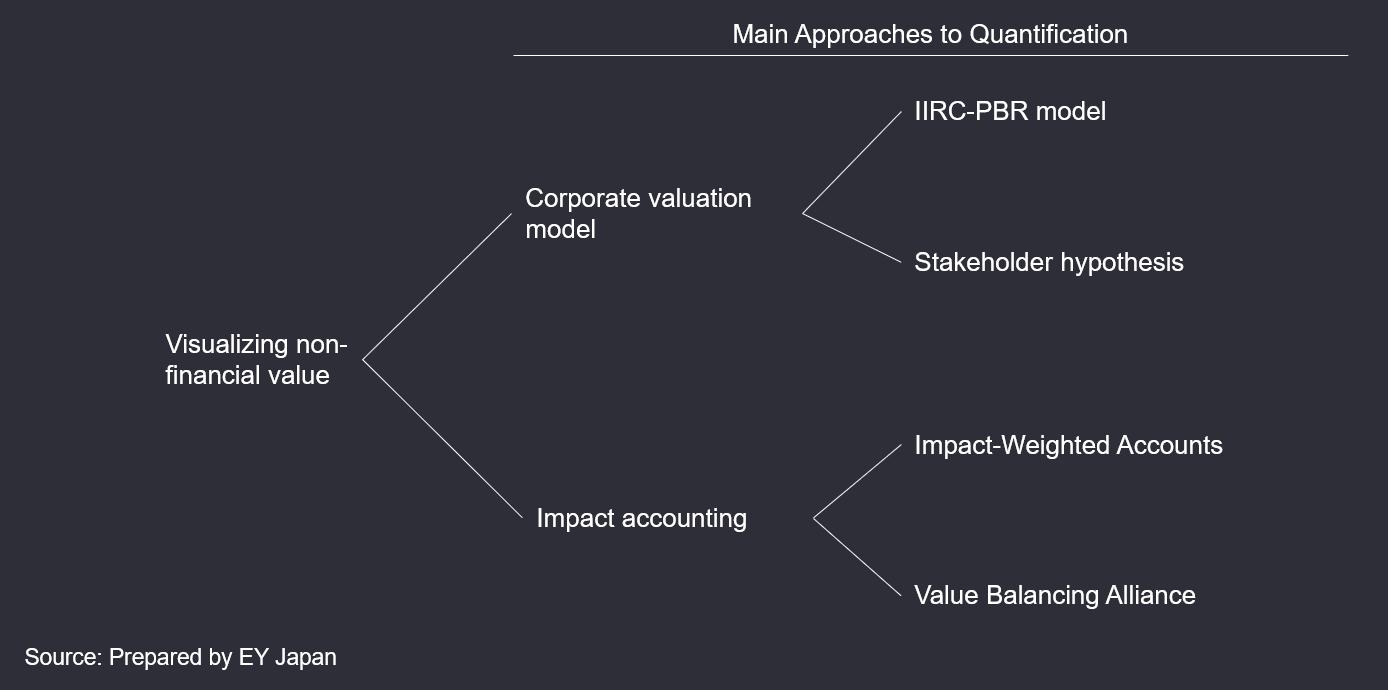

Partly because of this issue, in finance and accounting today, human capital is not necessarily evaluated in terms of its hypothetical purchase or selling price. Instead, several companies have begun to trial the following methods as a way to visualize the contribution of human capital to corporate value (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Visualizing Non-financial Value

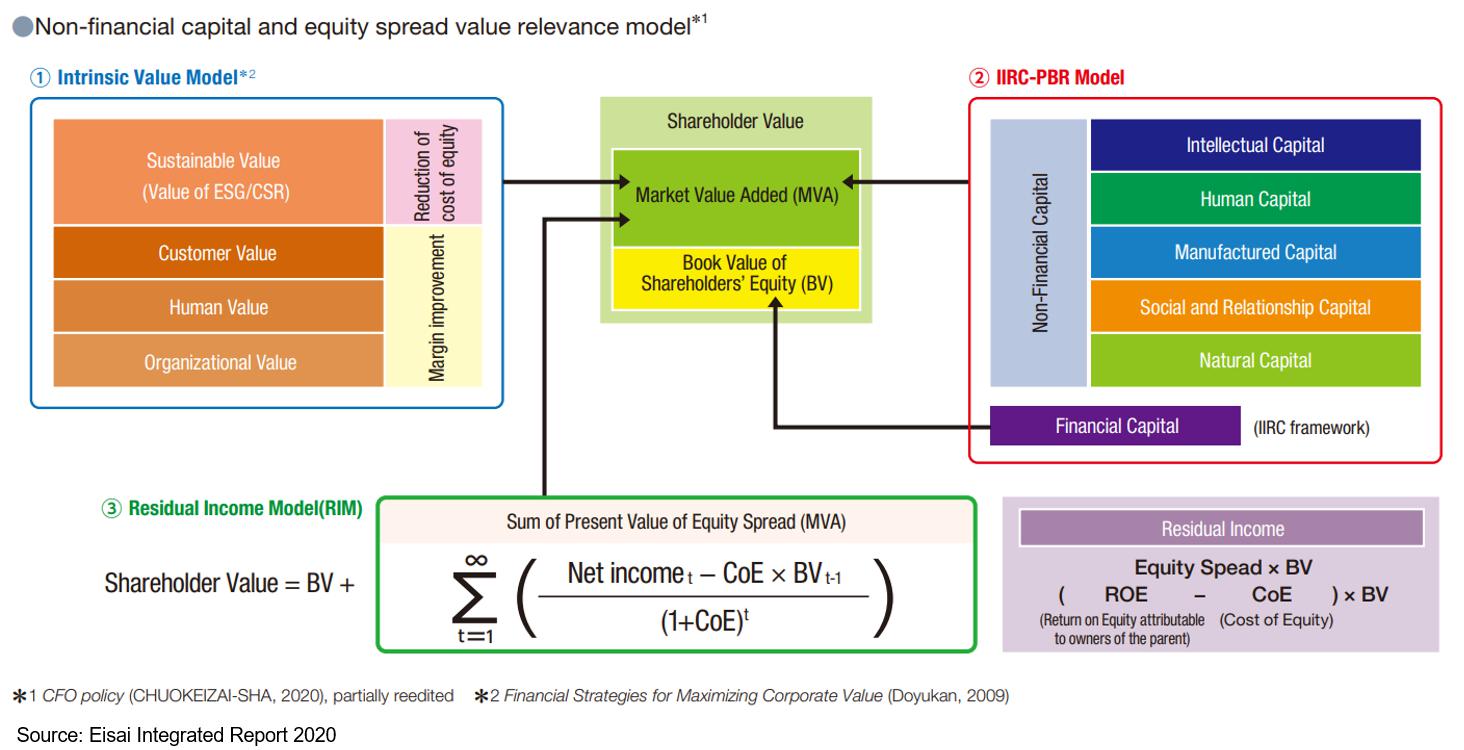

Two leading methods are the IIRC-PBR model and Impact-Weighted Accounts. Let us begin with an explanation of the IIRC-PBR model. The initial approach that would later become the IIRC-PBR model was already in evidence in the “Synchronization Model of Non-financial Capital and Equity Spread” (Yanagi et al. 2016)[12], and Professor Ryohei Yanagi (former CFO of Eisai Co., Ltd. and Visiting Professor of Waseda University), a leader in this field, subsequently published numerous related proofs and papers (Fig. 6). The key point of the IIRC-PBR model is its attempt to clarify what kind of effect intangible assets, including human capital (intellectual capital, human capital, manufacturing capital, social and relationship capital, and natural capital, as defined by IIRC[13]), have on the price-to-book ratio (PBR) and return on equity (ROE) over time. Specifically, by performing a regression analysis of ESG metrics with corporate value-related financial indicators, it derives relationships between non-financial and financial results.

Figure 6: Non-financial Capital and Equity Spread Value Relevance Model

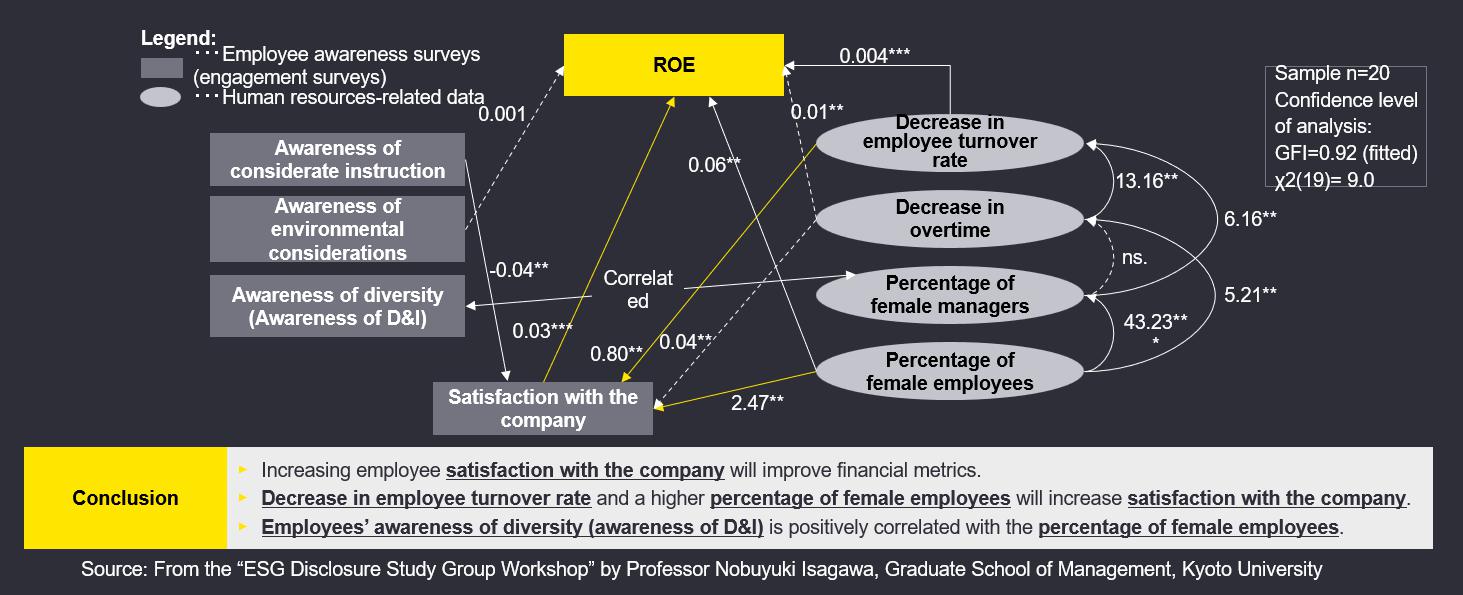

Similar research has been undertaken by Professor Nobuyuki Isagawa of Kyoto University. Professor Isagawa focuses specifically on human capital, endeavoring to clarify the relationship between human capital-related metrics (e.g. male and female employment rates, training expenses, and employee satisfaction metrics) and financial indicators such as ROE and ROIC (return on invested capital). He refers to this as the stakeholder hypothesis. While both of these approaches analyze how investment in non-financial capital affects financial results, Professor Isagawa verifies the impact path from human capital-related metrics to financial results. This impact path analyzes both direct and indirect impact, as well as mutual relationships between measures (e.g., how workplace environments that are accepting of diversity can encourage the advancement of women and how this is linked to the promotion of research and development, thus contributing to revenue (Fig. 7)).

Figure 7: Human Capital-related Metrics and ROE

The author has implemented each of these approaches as part of client services. Several issues have come to light through practical application. First, there is an overwhelming lack of HR-related data, making it difficult to derive advantageous results from analysis. To begin with, how many companies in Japan keep at least five years of historical data on how much they invest in training companywide, each year, together with employee satisfaction metrics? With wage calculation systems often differing by country or place of business, it is rare for the company headquarters to maintain HR data that is both integrated and comprehensive. As a result, there is often not enough data at present to even begin an analysis. (Going forward, progress on disclosure is expected to facilitate the accumulation of data.) Second, the interpretation depends on the share price. It is easy to accept any interpretation when the share price is rising, but difficult to derive a positive result when the share price is falling. Many factors affect share price, besides just human capital and ESG, but it is extremely difficult to eliminate this noise from the data. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, both ESG data and share prices moved in ways completely unlike the preceding trends. Factors such as sudden corporate scandals and international economic conditions may also cause abnormal share price movements but are unrelated to human resource-related information. Third, this analysis examines correlation, not cause, and therefore does not guarantee that management can reproduce the results in the future. Even if past results seem to indicate that promoting diversity contributes to revenue several years down the track, it is difficult to claim that the same thing will happen into the future. Therefore, even if it is tempting to treat ESG metrics as leading indicators of future revenue, it is vital that the company concerned lays out a strategic scenario indicating how this is to happen.

The usefulness of this analysis lies rather in facilitating the verification of what sort of initiatives tend to promote management strategies and corporate value — and what activities should be reconsidered — for companies that are already engaging in some form of sustainability and ESG initiatives. This will enable ESG investment to be consistent with the company’s strategies and management plans and the reallocation of resources. In addition, it will make it easier for the company to communicate these endeavors in combination with its envisaged financial revenue scenario. In other words, it will be easier to present sustainability and ESG initiatives as investments that contribute to the future enhancement of corporate value, rather than simply costs. This may also lead to higher-quality IR activities and communication with stakeholders, enabling the company to explain mutual benefits in the context of reconciling interests between stakeholders.

Setting these considerations aside, the author believes it is important that both of the approaches described above are seen as ways to supplement basic information when companies plan out their strategies for the future. They should thus be used to enhance management quality as part of the basis for companies’ strategic scenarios, rather than as ways to increase the predictability of the future by interpreting historical data through induction.

Meanwhile, in an effort not necessarily connected to future revenue, an attempt is being made to gain an overall picture of businesses by visualizing social value, including externalities, in terms of accounting measures. This attempt is referred to as the Impact-Weighted Accounts Framework.

“Impact” signifies the changes and influence — both positive and negative — caused by companies to stakeholders, society, and the environment. It is interpreted as referring to longer-term effects than those described as “outcomes” on integrated reports and similar disclosures. The Impact-Weighted Accounts Framework aims not only to measure impact in terms of material resources but also to convert it into monetary amounts, thus incorporating impact into conventional income statements and balance sheets. The concept of impact-weighted accounts is said to derive from the Impact-Weighted Accounts (IWA) initiative launched in 2019 by Professor George Serafeim[14] of Harvard Business School (HBS) and others. The same year, HBS released a White Paper titled “Impact-Weighted Financial Accounts: The Missing Piece for an Impact Economy” (Serafeim et al. 2019)[15].

Economic activities that are predicated on social and environmental sacrifice are not sustainable. If a company’s impact on externalities such as human capital, social and relationship capital, and natural capital can be integrated into its financial statements, investors will be able to make investment decisions based on a consideration of all social effects and external non-economic factors, thus helping to resolve this issue. By internalizing externalities such as these, the IWA initiative is expected to facilitate an economy where funds are deployed to resolve social and environmental issues in line with market principles. Against this backdrop, impact-conscious investment methods such as impact investment and impact bonds are on the rise worldwide. Japan too has seen an increase in the number of startups raising money through impact funds aimed at resolving social issues. In more and more cases, these are also linked to regional revitalization measures.

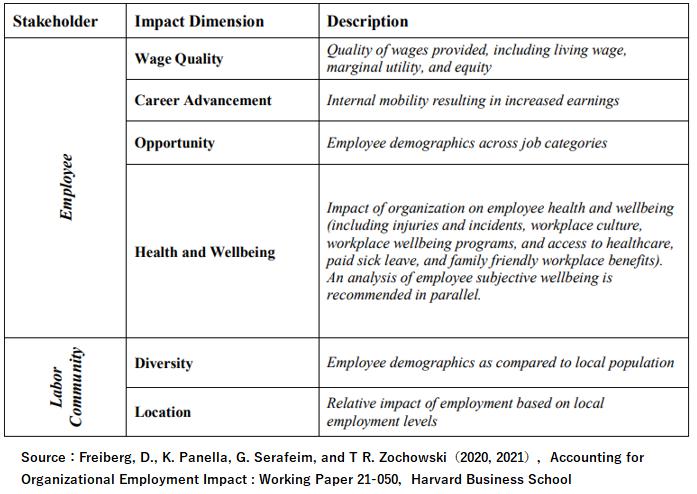

The IWA initiative proposed by Professor Serafeim focuses on three aspects: employees (employment), customers, and the environment. For employees (employment), the initiative focuses on the impact on employees and the labor community generated through employment. It perceives personnel expenses and the cost of welfare and benefits, which are recorded as expenses for accounting purposes, as sources of positive impact that contribute to employee motivation, health, etc. (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Descriptions of Employment Impact

It is thought that if investment in human capital contributes to employee health and motivation and, further, to building a positive relationship with the labor market, then this will lead to a sustainable improvement in the value of human capital. For management, the impact on employees (employment) provides input for appropriate decision-making on human resources strategies and the quality of investment in human capital.

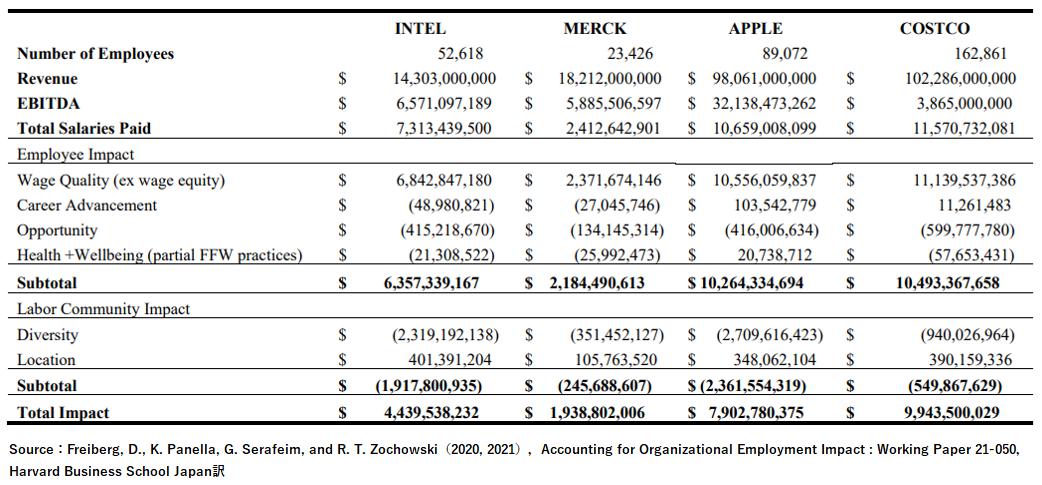

There are still few case studies of the trial of IWA for human capital, but Professor Serafeim has made the following estimates[16] (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Employment Impact-Weighted Accounts: Intel, Merck, Apple, Costco

According to these estimates, Costco has been the most efficient in generating employee (employment) impact (including in the labor community), with a total impact of approximately USD 9.9 billion from total salaries paid of approximately USD 11.5 billion (an impact-to-salaries ratio of approximately 86%). Meanwhile, Apple has been the most successful in investing in employees’ job satisfaction, generating a total of approximately USD 10.2 billion in areas including wage quality, career advancement, health and well-being from total salaries of approximately USD 10.6 billion (an impact-to-salaries ratio of approximately 91%). Going forward, the issue of how to integrate this information into accounting still remains. However, the level of employee impact contributes to employee retention, growth, and productivity, while the level of labor community impact is linked to advantages in securing talent. Analysis of its relationship with earning power in past years may reveal the competitive advantages of human capital.

At the same time, these figures do not represent future cash flows, so they cannot be discounted to present value to determine a company’s corporate value directly, nor can they be treated as internally generated goodwill (intangible assets). However, they do represent effective information for the purposes of investing in a sustainable society and management, if corporate value is regarded not simply in terms of shareholder value, but rather as the total value of the company, including its value (positive impact) for employees and all other aspects of society. Sustainable management refers to management that adapts to social change and builds long-term relationships of trust with diverse stakeholders.

5. Conclusion

An increasing number of large corporations are introducing job-type employment, and there is heated debate over whether human capital should be focused on job-type or membership-type employment. With the market undergoing dramatic changes, companies no longer have the freedom to recruit new graduates en masse and devote time to their gradual development. While it is not possible to generalize about the merits of either approach, there is certainly a growing awareness of the insufficiency of conventional forms of employment and HR systems. Meanwhile, while the debate raged for many years over whether “organizations follow strategy” or “strategy follows organizations,” recently, the view of “people before strategy”[17] has become increasingly popular. The position of “people” and the role of HR divisions are on the cusp of significant change. The perception of human resources is shifting from that of business resources to be managed to the leading part in value creation.

People differ from things in that they require time to change their skills and behavior; also, companies cannot own people. Finance is blind to value created over a long period of time, as it is not reflected in net present value (NPV), implying that it can be ignored. Moreover, there is no place in financial statements for unowned assets: this represents another blind spot of finance. The fact that human resources are not visualized through the financial statements, despite playing a core role in value creation and the main part in corporate strategy, suggests the potential existence of value of which both management and investors are unaware. What cannot be quantified cannot be managed. Today, attempts to quantify metrics relating to human capital have only just begun, and when, in a few years’ time, it becomes possible to manage these metrics a new dimension of competition will be born. Some companies will be intrinsically motivated to actively visualize their human capital and use this information to facilitate dialogue with capital markets (disclosure), while others may passively follow the demands of society, perceiving human capital as simply a cost without attaching any special significance to it. One investor characterized companies’ approach to people in this way: “Japanese companies tend to fence people in (like cattle), but leading global companies attract outstanding people (free range) by offering better environments.” People before strategy: It is no exaggeration to say that corporate value depends on the management of human capital. With disclosure regulation progressing in advance of companies’ ability to prove the value of human capital, the issue is whether or not senior management will be able to seize the initiative. The essence of corporate value lies in the intrinsic motivation of management and management skills.

[1] “Major policies of the Kishida Cabinet 01/ A New Form of Capitalism,” Prime Minister's Office of Japan website

https://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/policies_kishida/newcapitalism.html(September 9, 2024)

[2] “Publication of Revised Japan's Corporate Governance Code,” JPX Group website

https://www.jpx.co.jp/english/news/1020/20210611-01.html (September 9, 2024)

[3] A regulation that outlines how companies should disclose material other than financial statements on their annual reports (Form 10-K).

[4] “Recommendation of the SEC Investor Advisory Committeeʼs Investor-as-Owner Subcommittee regarding Human Capital Management Disclosure,” Investor Advisory Committee

SEC (2023), “Draft Recommendation of the SEC Investor Advisory Committeeʼs Investor-as-Owner Subcommittee regarding Human Capital Management”

https://www.sec.gov/files/spotlight/iac/20230921-recommendation-regarding-hcm.pdf (September 9, 2024)

[5] “Results of Public Comments Concerning Draft Reforms of the Cabinet Office Ordinance on the Disclosure of Corporate Affairs, etc.,” Financial Services Agency website (Japanese only)

https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r4/sonota/20230131/20230131.html (September 9, 2024)

[6] In the EU, civil society is always involved in policymaking.

[7] “The European Green Deal: Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent,” European Commission

https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (September 9, 2024)

[8] GAFA is an acronym for the four US tech giants Google (currently Alphabet), Amazon, Facebook (currently Meta), and Apple.

[9] Japan’s Corporate Governance Code was put into effect in 2015 to reform this aspect of governance.

[10] Mandatory consolidated financial reporting began in Japan in 1978, but the focus was still on non-consolidated results, and few companies disclosed their consolidated financial reports. Disclosure focused on consolidated financial results began in 2000 with the revision of the Securities Exchange Act (currently the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act).

[11] “Toward Ensuring Equal Employment Opportunities and Treatment for Men and Women,” Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare website (Japanese only)

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/koyou_roudou/koyoukintou/danjokintou/index.html (September 9, 2024)

[12] Yanagi, Ryohei, Hiroyuki Meno, and Takaaki Yoshino (2016), “Synchronization Model of Non-financial Capital and Equity Spread,” Gekkan Shihon Shijo (Monthly Capital Market Journal) 375, pp.4-13 (Japanese only)

https://www.camri.or.jp/files/libs/144/201703241647339179.pdf (September 9, 2024)

[13] The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) merged with the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) to form the current Value Reporting Foundation (VRF).

[14] George Serafeim, Harvard Business School

https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/profile.aspx?facId=15705 (September 9, 2024)

[15] Serafeim, George, T. Robert Zochowski, and Jennifer Downing (2019) “Impact-Weighted Financial Accounts: The Missing Piece for an Impact Economy,” White Paper, Harvard Business School

[16] Freiberg, David, Katie Panella, George Serafeim, and T. Robert Zochowski (2020, 2021) “Accounting for Organizational Employment Impact: Working Paper 21-050,” Harvard Business School

[17] Charan, Ram, Dominic Barton, and Dennis Carey (2015), “People Before Strategy: A New Role for the CHRO” Harvard Business Review, 2015

https://hbr.org/2015/07/people-before-strategy-a-new-role-for-the-chro (September 9, 2024)