Preventing the Two-Pillar Solution to International Taxation from Breaking the Camel’s Back

October 31, 2023

R-2023-016E

The OECD’s two-pillar solution seeks to redress outdated international tax rules for corporate income taxation and ensure that big multinationals pay their fair share of taxes. But the complicated rules mean that firms in jurisdictions that do not adopt the new rules might have an advantage over those burdened with heavy compliance obligations.

* * *

On October 11, 2023, the Task Force of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS (base erosion and profit shifting) approved the release of the text of the Multilateral Convention (MLC) to Implement Amount A of Pillar One. The document is intended to enable a “new taxing power” that will allocate the tax base of large multinational enterprises (MNEs) with revenues over 20 billion euros and a profit margin of at least 10% to market jurisdictions. The agreement has not yet been opened for signature, as there are still a few disagreements, but it is a milestone in a series of works, called BSPS 2.0, that began in 2018, and it could lead to positive developments in international tax reform.

The OECD announced in a July 2022 press release that the signing ceremony would take place by the end of 2023. However, the US government is not expected to sign the convention this year since the United States has issued a new public comment request deadline of December 11 on the draft articles published by the OECD.

Japan enacted a 15% global minimum tax for large multinationals (sales over €750 million) as part of its fiscal 2023 tax reform. This represents a major revision of the 1965 Corporate Tax Law, adding a new chapter to the law. It is intended to implement the GloBE (global anti-base erosion) rules, agreed to by 140 countries of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, aimed at putting a floor on the race to the bottom in corporate taxes through a coordinated approach by governments. Germany, France, Britain, and Australia are also preparing domestic legislation. Singapore, an investment hub, is reported to be a year behind. This trend, too, will have positive implications for international tax reform.

However, the complexity of the rules presented by the OECD could become an obstacle. The MLC is 200 pages long for the text of the convention alone, and there are 600 more pages in the explanatory document—for a total of over 800 pages.

The Pillar Two GloBE documents are also detailed and extensive, including the Model Rules (70 pages), Commentary (230 pages), case studies (50 pages), two sets of guidance (111 and 90 pages, respectively), and the GloBE Information Return (82 pages). These total some 700 pages.

Given the ongoing efforts of countries to simplify their national tax laws, and the fact that politicians have emphasized a “solution through a simplified system” at every turn in the course of the discussions on a two-pillar solution, it seems odd that the international community has concluded that it needs to rely on such extensive documents.

For Japan, a country with the second-largest number of MNEs after the United States deriving 77% of its corporate tax revenue from such companies, the issue of administrative and compliance burden is critical.

In the following, I will address issues surrounding the compliance costs of applying the 15% global minimum tax rule and their implications for the competitiveness of MNEs.

Which Countries Are Affected?

For the MLC to enter into force, 30 countries with at least 600 “points” must deposit their instruments of ratification. A total of 999 points are attributed to countries with “in-scope MNEs,” that is, MNEs to which the MLC Amount A regime applies. Thus, countries with high points are where giant and highly profitable MNEs are located.

Table 1. Countries with Giant, Highly Profitable MNEs (by “Points”)

|

Country |

Points |

Country |

Points |

|

United States |

486 |

India |

15 |

|

China |

94 |

Netherlands |

15 |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

88 |

Spain |

15 |

|

France |

56 |

South Korea |

11 |

|

United Kingdom |

49 |

Belgium |

9 |

|

Japan |

47 |

Canada |

6 |

|

Germany |

45 |

Denmark |

4 |

|

Switzerland |

34 |

Mexico |

2 |

|

Ireland |

21 |

Saudi Arabia |

2 |

|

Other Jurisdictions |

0 |

Source: Annex I: Points Attributed to Jurisdictions for Purposes of Certain Provisions, Table 2 of the MLC.

According to the OECD CbCR (country-by-country reporting) database, there were 6,764 MNEs subject to the 15% global minimum tax in 2018. The country with the largest number of MNEs was the United States, with 1,641 MNEs, followed by Japan with 861. Some 70% of the world’s MNEs are concentrated in the top 10 countries.

Table 2. Countries with Large MNEs (by 2018 CbCR database)

|

Reporting Jurisdictions |

MNEs |

Reporting Jurisdictions |

MNEs |

|

United States |

1,641 |

India |

151 |

|

Japan |

861 |

Luxembourg |

147 |

|

China |

394 |

Italy |

139 |

|

Germany |

387 |

Switzerland |

138 |

|

United Kingdom |

387 |

Australia |

132 |

|

Korea |

245 |

Spain |

132 |

|

France |

232 |

Cayman Islands |

110 |

|

Canada |

220 |

Sweden |

103 |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

167 |

Austria |

82 |

|

Netherlands |

165 |

Brazil |

81 |

Source: OECD Corporate Tax Statistics, Fourth Edition (2022), Table 1

Competitiveness and Achieving a Level Playing Field

At this time, there is no prospect of the GloBE rule being incorporated into US law (see a press release from Republican members of the House Ways and Means Committee). This means that there will be no additional administrative/compliance burden for large US multinationals with respect to the 15% global minimum tax.

It is theoretically possible for a country that has enacted the GloBE rules to impose a 15% global minimum tax on a US company. But the Republican Congressional majority has proposed a bill to impose retaliatory taxation in such cases. Given such risks, few countries are likely to tax US multinationals that, by definition, are outside their tax jurisdictions. Inasmuch as the United States is not a country that is driving a race to the bottom, the author is of the opinion that extrajurisdictional taxes should not be levied on US multinationals, as well as on MNEs in other jurisdictions.

Since most Japanese MNEs are not thought to be engaged in aggressive tax avoidance, the 15% global minimum tax was viewed as benefiting Japanese companies, as it would ensure a level playing field with foreign multinationals pursuing tax minimization strategies. One should note, however, that compliance costs fall equally on MNEs, regardless of whether they engage in tax minimizing strategies.

For Japan, which has the second-biggest number of large MNEs, the issue of compliance costs for businesses and administrative costs for the National Tax Agency is likely to become a greater factor in determining competitiveness than any increase in the tax burden.

Table 3. Overview of Large MNEs in Selected Countries

|

Jurisdictions |

Number of MNEs |

Number of CbCR subgroups |

Effective tax burden of foreign subsidiaries |

|

United States |

1,641 |

126,017 |

10.8% |

|

Japan |

861 |

42,211 |

23.5% |

|

China |

394 |

|

|

|

Germany |

387 |

33,742 |

14.0% |

|

United Kingdom |

387 |

36,500 |

18.7% |

|

Korea |

245 |

7,162 |

31.4% |

|

France |

232 |

35,901 |

27.6% |

|

Canada |

220 |

16,040 |

15.6% |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

167 |

27,548 |

20.6% |

|

Luxembourg |

147 |

12,212 |

9.7% |

|

Australia |

132 |

6,379 |

14.2% |

|

Singapore |

79 |

6,160 |

27.7% |

Source: Created by the author based on the OECD CbCR database.

A Complex, Costly System That Does Not Boost Tax Revenues

International tax expert Mindy Herzfeld of the University of Florida has noted, “the Pillar Two revenue estimates show how little revenue this very complex regime can raise” (Tax Notes International, August 28, 2023).

Regarding the impact of GloBE rules on tax revenues, the Ministry of Finance (Zeisei Kaisei Taiko, p. 111) estimates that the GloBE income inclusion rule (IIR), which Japan has already legislated, will have zero impact on raising tax revenue.

The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation of the United States, which does not plan to introduce GloBE rules, published an analysis in June 2023 stating that Pillar Two will result in a huge revenue loss of $122 billion over 10 years—an average of $12.2billion per year. The UK Treasury, meanwhile, estimates that GloBE rules will generate £2,085 million (US$2,384 million) in additional revenue in 2025.

In judging whether such a complex system is acceptable or needed, the following differences must be kept in mind. The design objective of the 15% global minimum tax is to stop the race to the bottom, not to calculate the just and correct income of MNEs, which was the goal of the controlled foreign company (CFC) anti-tax haven rules to combat tax avoidance under national tax law.

If the complex GloBE rules were intended to calculate the just and correct amount of taxable income of MNEs, they would create a duplication for countries, like Japan, that already have national CFC rules.

But that is not the purpose of the GloBE rules, which are only intended to ensure that MNEs pay at least 15% in corporate taxes and thus eliminate incentives for countries to lower their corporate tax rates and encourage inbound investment. In that sense, the complex GloBE rules could become a factor that hinders the achievement of their main objective.

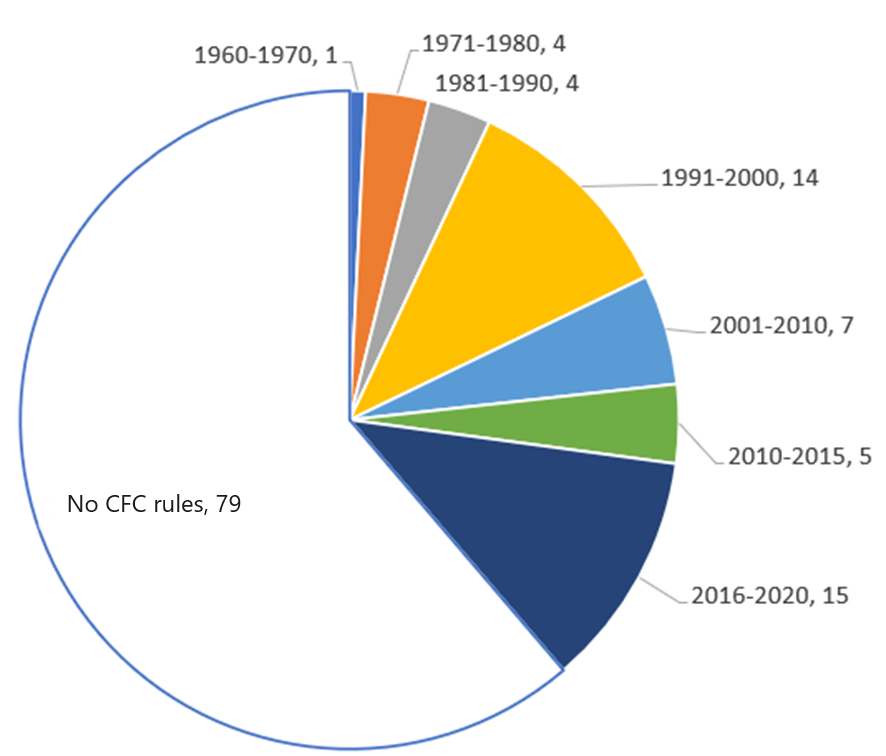

Countries That Have Adopted CFC Rules

Perhaps an even bigger concern is that most countries do not have much experience with comprehensive CFC taxation, that is, the taxation of MNEs’ foreign subsidiaries in the country of the parent company. Tellingly, the OECD failed to reach a consensus among members on CFC taxation in its 2015 BEPS final report. This was partly because of varying levels of national experience with CFC rules.

National CFC rules were first introduced in the United States in 1962, followed by Germany in 1972, Canada in 1976, Japan in 1978, France in 1980, and Britain in 1984. Many European countries that have national CFC rules today introduced them quite recently.

The tax regime cited in Article 7 of the EU Council’s Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD) provides for the limited inclusion of transactions of foreign subsidiaries, namely, when certain financial income or “non-genuine arrangements” for obtaining a tax advantage are involved. On the other hand, CFC rules in Japan and Subpart F in the United States provide for the inclusion of general, broader transactions of foreign subsidiaries and certain carve-outs. The GloBE income inclusion rule is akin to the latter type of inclusion.

History of National CFC Rules

Source: Created by the author based on OECD data (2020).

Pushing Companies to the Breaking Point

The public consultation document for Globe Information Return (2022) claims that the “Inclusive Framework has sought to strike an appropriate balance between administrative requirements and compliance concerns” (paragraph 3).

The documents introducing the GloBE rules, though, total some 700 pages, as mentioned above, and the content is extremely complex. The “Calculation of Effective Tax Rate and Top-Up Tax Amount,” for example, requires information for more than 30 subdivisions. Some subsections require MNEs to prepare up to 23 different types of information.

MNEs are already burdened with various information and compliance obligations, such as simultaneous documentation of transfer pricing taxation and CFC taxation. In Japan, annex 17(3) of the schedule of corporate tax returns for anti-tax haven information obligations requires a description of nearly 20 items and nearly 10 balance sheets and other supporting documents to be prepared for each group company.[1]

The information obligations for the 15% global minimum tax will only add to the existing administrative burden. The tax must therefore be considered not just in terms of its scope but also from the viewpoint of the costs of compliance and administration for MNEs.

Potential Responses

What are some steps that can be taken to alleviate such a burden? One option, drawn from the Japanese experience, would be to replace the consolidated tax system with a group relief system.

Japan’s fiscal 2020 tax reform abolished the existing consolidated tax system and replaced it with a group relief system to reduce the administrative burden of companies. According to the National Tax Agency’s FY2020 Tax Reform, in view of how it is used and how group companies are managed, the consolidated tax system (which treats the entire group as a single taxpayer, including the aggregation of the profits and losses of individual corporations within the group) will be simplified and reviewed from the perspective of reducing the compliance burden on MNEs and will be shifted to a group relief system under which each company calculates and reports its corporate tax amount individually, while maintaining the basic framework of profit and loss totalization achieved by the consolidated tax system.

Commenting on the reform in the Japan Tax Law Review, Waseda University tax law professor Tetsuya Watanabe noted that tax systems whose compliance burdens are excessive for taxpayers should, as a rule, not be introduced or maintained. He added that the same applies to the burden for tax administrators (“Corporate Taxation in the Age of Open Innovation,” Japan Tax Law Review, no. 51, p. 26).

In the 2023 tax reform, moreover, the scope of companies subject to the CFC rules was revised to reduce the effective tax burden rate from 30% to 27%, taking into account that the introduction of the GloBE rules would mean an additional compliance burden for MNEs. According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s explanation, nearly 4000 subsidiaries will re-excluded from the CFC rules.

These are some case studies of attempts in Japan to actively reexamine substantive provisions of tax laws in the light of the burdens they impose, and they may be serve as points of reference for other nations. Japan, given its large number of MNEs, is particularly sensitive to the relationship between taxes and the information obligations they incur.

Conclusion

MNEs are burdened with many information and compliance obligations, and this could have as much or an even bigger impact on their competitiveness than any additional taxes that may be levied under the two-pillar solution.

Given that the GloBE rules will not be legislated anytime soon in the United States, which has the world’s largest number of MNEs, other countries with many MNEs—Japan included—will naturally be sensitive to the impact of compliance burdens on the competitiveness of those companies.

Compliance is a complicated matter, and the costs can be enormous. Responsibility should not be left solely in the hands of the accounting or tax department; top management must understand and be actively engaged in addressing the issues. When considering a cross-border M&A strategy, for example, the board must understand how the two-pillar rules apply when adding a new foreign subsidiary and what the cost implications will be.

National governments and the OECD should continue their efforts to strike a balance between the objectives and the complexity of the rules. They may, for example, consider creating safe harbors for tax information requirements by compiling a “white list.” Germany is already taking steps in this direction.

For all its good intentions, the 15% global minimum tax must be applied in ways so that it does not become the final straw that breaks the backs of corporate camels.

[1] Footnote 29 of International Taxation in the Digital Economy (Interim Report of the “Study Group on International Taxation in the Digital Economy”), prepared by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry states: “As an example of the actual compliance costs under the current CFC rules, there was an opinion that the number of foreign subsidiaries subject to the system increased by a factor of 3 times and the number of man-hours increased 4-5 times compared with those before the 2017 revision.”

![[Policy Research] Water Minfra: A New Strategy for Water-Centric Social Infrastructure](/files_thumbnail/research_2023_Oki_PG_Mizuminhura_png_w300px_h180px.png)