A Consideration of Two Virtuous Cycles ――Necessary revisions to our narratives――

August 5, 2024

R-2024-009-E

Even if a virtuous cycle between wages and prices is achieved, it will fall short of expectations

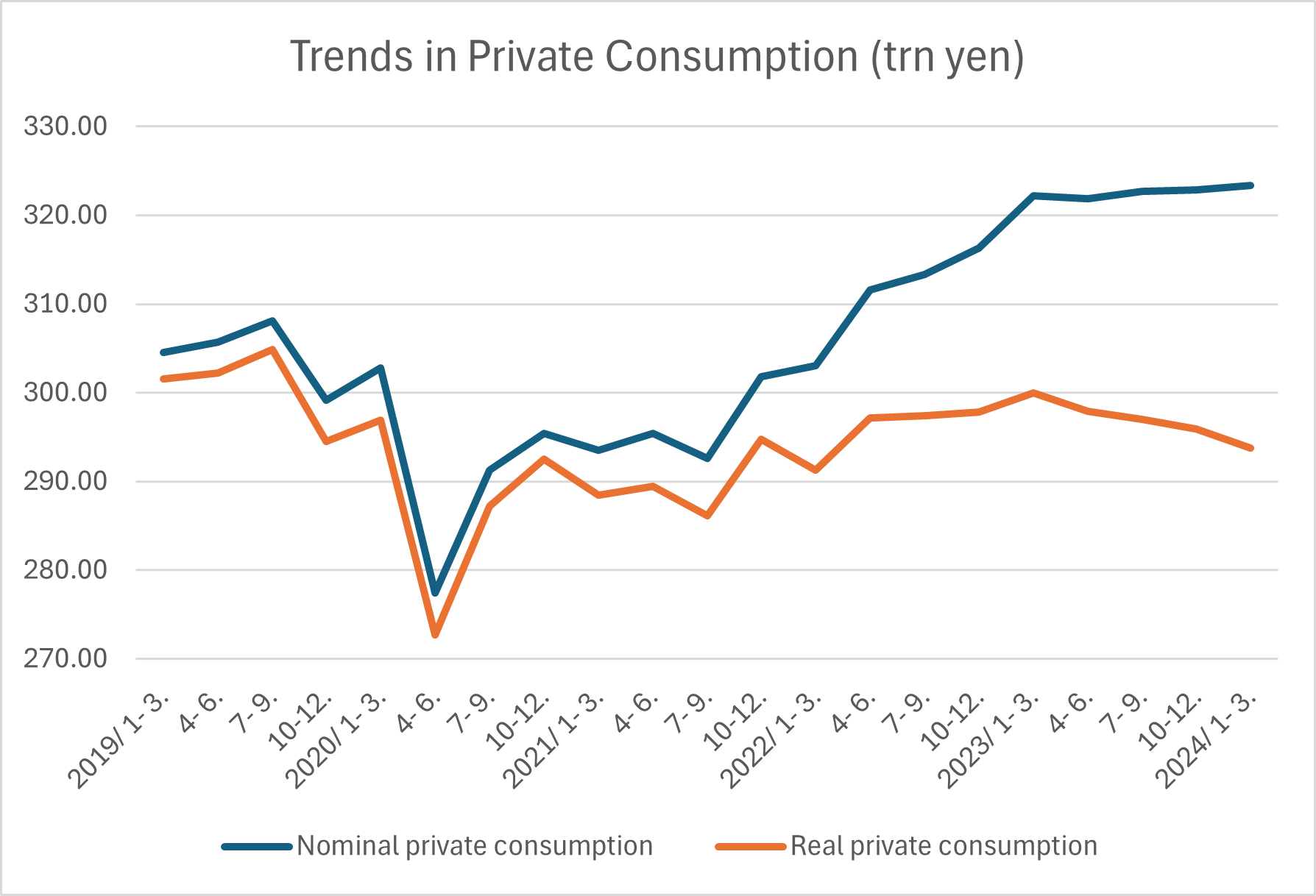

While talk of a virtuous cycle between wages and prices is nothing new, the actual data on wage and price movements shows that the consumer price index (CPI; excluding fresh food) has not only been above the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ’s) target of 2% year-on-year growth for more than two years, but year-on-year growth in scheduled cash earnings (based on firms with five or more regular employees) has also exceeded 2% on average for the nine months since July 2023. Based on this data, it seems safe to conclude that this virtuous cycle between wages and prices has nearly been achieved. However, there is nothing to indicate that most Japanese citizens are satisfied with the current state of affairs. This dissatisfaction is understandable, given that even if wages rise, the inflation rate has remained stuck at levels higher than expected, so that real wages have continued to decline for over two years. It is certainly true that this year’s annual spring labor-management wage negotiations have resulted in wage hikes of about 5.10%, so real wages could turn positive in the second half of this year. That said, especially since Japan is just coming out of a period in which private consumption was severely depressed by the pandemic, and then fell due to the subsequent increase in prices (Fig. 1), we do not expect the public to be particularly satisfied even if real wages reach positive levels and private consumption recovers somewhat.

Figure 1 Trends in Private Consumption (trn yen)

Source: Prepared by the author using GDP data.

Considering this further, since economics assumes that it is real income (real consumption) that defines economic welfare, it is somewhat strange that wages and prices, which are nominal values, would move in a virtuous cycle, i.e. even if wages increase 2%, if prices increase 2%, it is only natural that real consumption would not increase. This is likely due to the persistent narrative that deflation is to blame for the Japanese economy’s prolonged stagnation. In fact, it is widely known that the main objective of the second Abe administration’s efforts to revive the economy was to banish deflation through bold monetary easing. However, there was no concrete evidence for the claim that deflation was the cause of Japan’s economic slump.

Needless to say, an annualized drop in prices amounting to 5 or 10% will exacerbate the real debt burden (debt deflation) and have a significant negative impact on the economy as a result of corporate bankruptcies and other factors, as demonstrated during the USA’s Great Depression in the 1930s and Japan’s Showa Depression of 1930-31. We think it unlikely, however, that Japan’s deflation in recent years, which is less than 0.5% annualized, would have such a massive impact (long-term real interest rates have actually fallen heavily)[1]. We find the observation of Tsutomu Watanabe, a Professor at the University of Tokyo, that the culprit was less a drop in prices than that the norm of keeping wages and prices frozen had impeded resource distribution to be somewhat convincing, but it does not hold up to scrutiny as the main cause of a long-term stagnation[2]. A recent survey carried out by the BOJ[3] found that “sluggish prices” was the fifth-most common factor that Japanese companies cited as leading to more or less activity for their businesses, so it would be going too far to claim that this is the main factor behind the prolonged slump.

We suspect that macroeconomic ideas dating back to the period in which deflation began in Japan somehow influenced the creation of this narrative blaming the economy’s long-term slump on deflation. In the period from the 1990s to the global financial crisis (GFC; known in Japan as the “Lehman shock”), the new Keynesian economics framework dominated the macroeconomics field around the world, particularly in the U.S. This model coopted the “Keynesian” title but simply tacked on the theory of price stickiness (and monopolistic competition) to neoclassical economics and is unable to explain long-term depressions in cases other than those in which real interest rates are stuck at high levels due to deflation. Conversely, as long as a protracted depression continued in Japan, deflation was likely considered to be the cause. In fact, since the GFC, even the U.S. and Europe experienced prolonged slumps, which led to the concept of “secular stagnation” as an explanation for long-term recessions—a theory spearheaded by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. Thanks to this theory, observers accepted the view that factors other than deflation such as the after-effects of GFC, falling populations, and aging societies could also be behind protracted stagnations. However, this theory emerged about one year after Abenomics began[4].

Signs that a Virtuous Cycle between Productivity and Real Income is Feasible

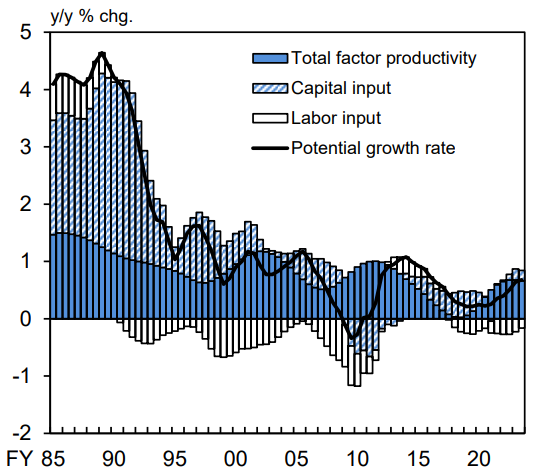

What we really need is a virtuous cycle between productivity and real income. After all, although it may be obvious, real income cannot increase in a sustained way without an increase in productivity. Japan, however, lost out on a boost in productivity during the past 30 years, which is clearly demonstrated by the sharp drop in its potential growth rate from the 4-5% range through around 1990 to the 0-1% range (Fig. 2). As a result, Japan’s per-capita GDP (based on USD) fell from the third-highest in the world 30 years ago, in 1994, to 32nd last year[5].

Figure 2 Potential Growth Rate

Source: Bank of Japan, “Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices” (April 2024)

We believe this drop in productivity growth can be attributed to many factors, including a slump in capital investment and the decline in the working-age population resulting from a decreasing overall population and an aging society; it is not possible to explain this decline by pointing to a single factor[6]. Personally, however, the author believes that the financial crisis in 1997-98 had an extremely significant impact. During this period, even some of Japan’s leading companies in the iron and steel, chemical, and general construction sectors were in danger of bankruptcy, and somehow managed to avoid failure by terminating regular employees, which was taboo back then. Ever since then, Japanese companies have been avoiding the risk of bankruptcy as their main management objective, and have endeavored to cut fixed costs, by replacing regular employees with non-regular workers, reining in personnel costs, curbing capital investment, and taking other measures, while also building up internal reserves. As a result, they have significantly reinforced their financial positions, but investments in both physical and human resources have been inadequate, and productivity fell sharply[7].

That said, recently there have been changes in this corporate behavior, one of which is actually a significant rise in wages. Until now, when corporate earnings have improved, companies may have increased bonuses, which can be cut in line with earnings, but have shown a strong tendency to avoid raising base salaries. However, over the past two years, we have seen a notable increase in wages, particularly base salaries (increases of which had been nearly nonexistent for more than two decades, but this year, base salaries has increased by around 3.5%). We are also beginning to see aggressive capital investment plans. According to the Cabinet Office’s Survey on Corporate Behavior, growth in capital investment plans over the next three years will be the highest since the bubble period (Fig. 3). We can attribute this to heightened (albeit still modest) expectations for growth in the industries to which these companies belong.

Figure 3 Medium- and Long-Term Growth Expectations and Business Fixed Investment Plan (%)

Source: NLI Research Institute, “Japan’s Economic Outlook for Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025 (May 2024)”

Needless to say, these are just signs of changes, and are not enough to justify a declaration that a virtuous cycle between productivity and real income has begun. In addition, even if a virtuous cycle has started, it is not clear what would be driving it. One of the author’s hypothesis at this point is that, now that about 25 years have passed since Japan’s financial crisis in 1997-98, the generation of managers who experienced the trauma of layoffs has been replaced by a new generation. Another possible factor is that globally, macroeconomic policy is shifting from an emphasis on monetary policy to a revival of industrial policy. Even in Japan, not only is the government pushing DX and GX, but changes in the geopolitical environment have encouraged efforts to attract semiconductor factories. The question now is whether these initiatives will also raise motivation in the corporate sector.[8]

More flexibility for 2% price target

As we previously discussed, a virtuous cycle between wages and prices has nearly been achieved. However, while the BOJ has ended its negative rate policy, it continued to keep rates at zero until the end of July, which was one factor behind the ultra-weak yen. We attribute this to the BOJ’s persistent focus on this 2% figure. While the author is relatively optimistic that inflation can be sustained at 2%, predicting future prices is extremely difficult, so if the BOJ wants to avoid errors at all costs, it is understandable that it is not particularly confident that inflation can remain at 2%.

This then brings us back to the problem of why inflation must stand at 2%. There was no room to even question this while the narrative was alive and well that the Japanese economy’s prolonged stagnation was due to deflation. After all, according to this narrative, the Japanese economy would recover and people’s lives would become prosperous once inflation reached 2%. However, after more than two years of inflation exceeding 2%, we now know that people’s lives actually become more difficult, and thus it is only natural to cast doubt on the need for 2% inflation. If we were to venture a guess, we would say this 2% target remains not because it is desirable for the average citizen, but because the BOJ needs it.

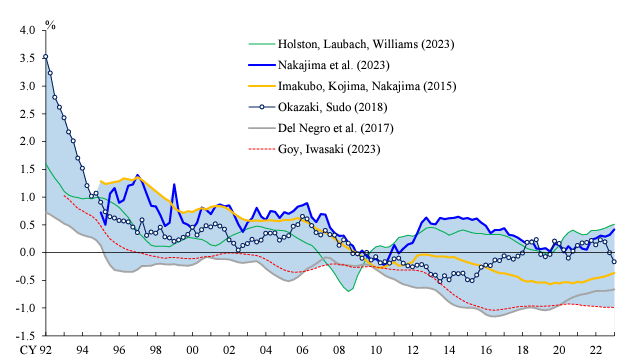

The neutral rate is a key concept when thinking about monetary policy. This is equivalent to the sum of the underlying inflation rate and the natural rate of interest, i.e. the real interest rate at which domestic savings and investment balance out. It essentially refers to rates when the economy is experiencing neither a slowdown nor rapidly accelerating growth. Estimates of Japan’s natural rate of interest are, on average, slightly negative (Fig. 4), so an underlying inflation rate of 2% would result in a neutral rate in the 1.5-2.0% range. We should note, however, that since estimating the natural rate of interest results in massive disparities, estimates of the neutral rate will inevitably be very uncertain.

Figure 4 Estimates of the Natural Rate of Interest for Japan

Source: UEDA, Kazuo. “Virtuous Cycle between Wages and Prices and the Bank of Japan's Monetary Policy,” Speech at a Meeting Held by the Yomiuri International Economic Society in Tokyo, May 8, 2024.

If the neutral rate is in the 1.5-2.0% range, then the BOJ would have room to lower rates in the event of a negative shock to the economy. However, if the underlying inflation rate is zero, the neutral rate would be negative, leaving no room for a rate cut. This is the situation Japan has found itself in since the 1990s. The BOJ needed 2% inflation to break out of this. Of course, we only have to remember the GFC to realize that, while the BOJ’s ability to respond to difficult economic times is clearly essential for regular citizens, the 2% target is first and foremost necessary for central banks (BOJ)[9]. In fact, the idea that the inflation target should be zero or higher in order to create room for rate cuts in the event of a downturn is often known as the “buffer theory.”

However, if the 2% target is a buffer, then there is no need to stick to this figure with such persistence that the public’s best interests are sacrificed. Leaving aside a situation in which a rate hike would run a large risk of returning to deflation, if inflation in the 1.5-2.0% range or more can be expected for some time, then the BOJ should take a more flexible stance by allowing for a gradual increase in rates. On this point, although some economists believed that even when there was no prospect of 2% inflation, the inflation target should be lowered to about 1%, the author did not agree. We would be concerned that the defeatist attitude that permits a reduced target simply because the target cannot be achieved would lead to further reductions in inflation forecasts. We want to stress that it is precisely because inflation has surpassed 2% for two years that the BOJ has room to take a flexible approach[10].

[1] For example, Claudio Borio et al. in “The Cost of Deflations: a historical perspective”, BIS Quarterly Review, March 2015 stated that there is only a “weak association” between deflation and economic growth when excluding exceptions such as the Great Depression.

[2] Over the past two years, the frequency of price revisions for individual products has accelerated rapidly, and there are greater discrepancies in relative prices, but at least at this point, there is little evidence that this has boosted the Japanese economy’s growth potential.

[3] Bank of Japan, “Results of the ‘Survey regarding Corporate Behavior since the Mid-1990s’” (May 2024). This survey found that respondents pointed to (1) the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) bubble burst and ensuing financial crisis, (3) global financial crisis, (4) declining and aging population” as the events and factors that led to domestic businesses being more or less active more often than they blamed “sluggish prices.”

[4] Summers first laid out his secular stagnation theory in an address he gave at a meeting held by the IMF in November 2013. The main ideas behind his address were subsequently compiled in Lawrence Summers, “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero lower Bound,” Business Economics, 2014.

Please refer to the August 2023 Review, Economic Policy Thinking since the Great Recession (1): The Backlash against Neoliberalism for a discussion of the changes in economic thought during this period.

[5] In addition, there was much discussion when Germany overtook Japan last year as the world’s third-largest economy in terms of the scale of nominal GDP, pushing Japan down to fourth place. However, we think this was likely due to increased JPY depreciation.

[6] For excellent sources of information on productivity in the Japanese economy, we recommend Tsutomu Miyakawa, Seisansei to wa nani ka (What is productivity?) (Chikuma Shinsho, 2018); Masayuki Morikawa, Seisansei: Gokai to shinjitsu (Productivity: Misunderstandings and reality) (Nihon Keizai Shinbun Shuppansha, 2018); and Kyoji Fukao, Sekai keizaishi kara mita nihon no seicho to teitai (Japan’s growth and stagnation as seen from a history of world economies) (Iwanami Shoten, 2020).

[7] On this point, see Chapter 3 of Hideo Hayakawa, Kin’yu seisaku no gokai (Misunderstandings of monetary policy) (Keio University Press, 2016).

[8] On this point, the author is very intrigued by the recent rapid expansion in Japan’s “digital deficit,” when the import of digital services and products surpasses their export. We see this as one of the factors behind the yen’s weakness, as we discussed in a December 2023 edition of the Review, Enyasu ga tomaranai riyu (Reasons for the yen’s ongoing depreciation), Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research website (tkfd.or.jp). At the same time, however, this is also a sign that Japanese companies are seriously grappling with DX.

[9]At the same time, estimating an inflation rate that benefits the public requires creating a model that can define economic welfare and estimating the optimal inflation rate. This often results in the conclusion that (1) the optimal inflation rate is not zero, but a slightly positive figure, but (2) it is not clear how far above zero it should be. Of these, (2) is a result of the general nature of the optimization problem, where the target function is flat above and below the optimal value so that even if the optimal inflation rate exceeds (undercuts) about 0.5%, it has little effect on economic welfare.

[10] However, the government and BOJ’s joint statement in January 2013 called for 2% inflation, so the BOJ cannot simply introduce more flexible operations at its own discretion. As we have seen with interventions in the FX market, if the government also wants to curb the yen’s excessive weakness, it should come to an agreement with the BOJ on flexible management of a 2% target and make an announcement to this effect.