The Two Income Barriers: How Do We Address Them?

March 31, 2025

R-2024-096E

The Democratic Party For the People (DPFP) has announced a policy platform titled “Increasing Take-home Pay. Moving Japan with ‘Solutions over Confrontation’” (DPFP 2024). One of the pillars of this platform is the “Reiwa-Period Income Doubling Plan,” which aims to achieve an economy where salaries and pensions increase. Specifically, the DPFP plans to raise the total basic deduction from 1.03 million yen to 1.78 million yen based on the 73% increase in the minimum wage since 1995. It lists the review of Category III insured persons as one of the essential issues that must be addressed to eliminate the “income barriers” (nenshu no kabe).

The DPFP’s policy proposal has sparked vigorous debate over income barriers. To begin with, it should be noted that there are two income barriers. The first barrier is the decline in take-home pay, despite any increase in income. The second barrier is the increase in tax burden when prices rise, even if there is no change in real income.

Based on the above, this paper considers how to confront these two barriers. To address the first barrier, radical reform is needed concerning the burden of social insurance premiums for people who have become a dependent spouse through marriage. To address the second barrier, it is vital to ensure that taxpayers’ actual tax burden does not change when prices rise. It is therefore necessary to adjust the burden based on the consumer price index. The consumer price index has increased by 13% since 1995, when the taxable income threshold was revised. This should serve as the baseline for raising the taxable income threshold. According to the DPFP’s proposal, a 73% increase is needed, raising the taxable income threshold from 1.03 million yen to 1.78 million yen based on the increase rate of the minimum wage. It is essential that any review of the taxable income threshold is based on public consensus rather than descending into a back-and-forth between opposing claims.

The First Income Barrier

The first income barrier refers to the decline in take-home pay, despite any increase in nominal income. In Japan, this barrier exists in the form of social insurance premiums, a burden that arises when the income of a dependent spouse exceeds a certain threshold. This leads to a decrease in the level of take-home pay after deducting taxes and social insurance premiums.

This issue has been labeled the “1.06 million yen barrier” or the “1.30 million yen barrier” and various explanations and discussions have been presented (including by the Japanese government’s online Public Relations Office), but the essence of the problem lies in the existence of so-called “Category III insured persons.” If a married person earns an annual income of less than 1.30 million yen and less than half of the annual income of their spouse, they are referred to as a Category III insured person and their insurance premiums are borne by the spouse (a Category II insured person), meaning they do not have to bear the burden themselves.

In other words, if the income of a Category III insured person exceeds 1.30 million yen, they become subject to a new burden of social insurance premiums, resulting in a decrease in take-home pay after deducting taxes and social insurance premiums. This is the essence of the first income barrier. If their income reaches 1.30 million yen or above, the Category III insured person becomes either a Category I or Category II insured person. Depending on their type of employment, they will join either the National Health Insurance and National Pension system or the social insurance (Employees’ Health Insurance and Employees’ Pension Insurance) offered by their company, bearing the burden of social insurance premiums.

By contrast, the “1.06 million yen barrier” arises before a person’s annual income reaches 1.30 million yen but after it reaches 1.06 million yen. It is at this point that a person becomes subject to enrollment in social insurance. Specifically, the obligation to pay health insurance and public pension premiums applies when (1) the number of employees in the company is 51 or more, (2) the person regularly works for at least 20 hours per week, and (3) the person is not a student. Although social insurance premiums are shared equally between the employer and employee, the 10% health insurance premium together with the 18.3% public pension premium result in a total of 14.15%, even when halved. This burden becomes heavier when combined with personal income taxes.

The first income barrier is therefore a problem unique to Category III insured persons. This is because unmarried individuals are classed as either Category I or Category II insured persons and are obligated to pay social insurance premiums regardless of their income. If Category III insured persons are actually reducing their working hours — in other words, refraining from work — to avoid this barrier, then the system that allows Category III insured persons to uniquely avoid paying social insurance premiums until they earn a certain level of income should be abolished.

The crux of the problem, as indicated above, is the heavy burden of social insurance premiums. This is a common issue regardless of the type of employment — for both Category I and Category II insured persons. The fact that this problem is particularly serious for low-income individuals is why it has been characterized as an income barrier.

In this regard, the issue should be addressed using measures that reduce the burden of social insurance premiums for individuals with income below a certain amount. Specifically, a system of tax relief should be established that corresponds to the burden of social insurance premiums on the eligible income, thus restoring the level of take-home pay after deducting taxes and social insurance premiums.

In addressing the first income barrier, it is important to consider not only the burden of social insurance premiums but also the level of pension benefits. By abolishing the system that exempts some Category III insured persons from paying social insurance premiums and expanding enrollment in employee pension insurance, the amount of the pension that employees receive will be significantly higher than under the National Pension system. This point should be examined together with any consideration of the first income barrier (Eiji Tajika 2020, 2023).

The Second Income Barrier

If the income tax deduction (taxable income threshold) is not increased in line with prices, taxable income will increase and the tax burden will rise. As a result, the tax burden increases even if real wages do not change. Higher tax rates may also apply, leading to an even greater tax burden. For workers, this results in higher taxes even though nothing else has actually changed. This is the second income barrier.

This barrier is also referred to as the “Achilles’ heel” of income taxation. The same issue also arises with corporate tax. Although price inflation causes the acquisition cost of assets to increase, asset depreciation and amortization expenses are calculated based on previous prices, resulting in tax depreciation that is less than the actual depreciation cost. This effectively inflates the taxable income of corporations and their tax burden rises as a result. For this reason, when prices are rising, it is essential to align the tax base with the price increase.

In Japan, the taxable income threshold is equal to the sum of the basic deduction and the salary income deduction. Income tax is payable on income exceeding that amount. When prices are rising, it is necessary to review (increase) the taxable income threshold in line with the rise in prices. At the same time, it is also necessary to review the income levels to which progressive tax rates apply. This paper considers the review of the taxable income threshold in the context of rising prices.

The key point is which price index to use. It is crucial to ensure that the real tax burden does not change, even if nominal wages increase due to inflation. To achieve this, it is necessary to use the consumer price index to raise the taxable income threshold in line with price increases, thereby maintaining a constant level of post-tax real income.

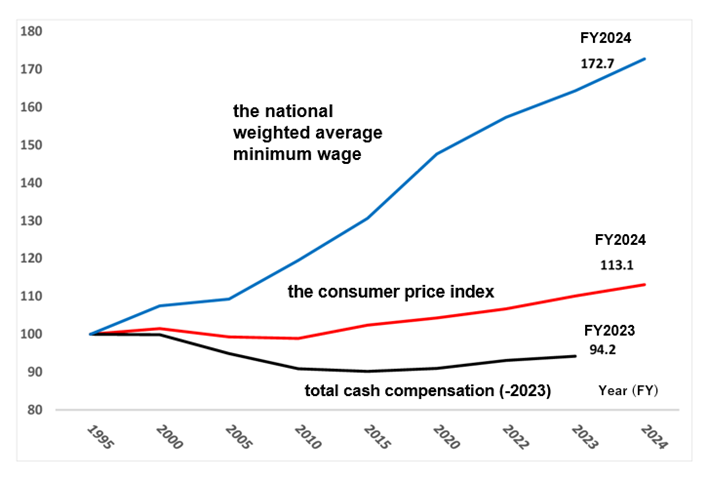

Figure 1 shows the trend in the consumer price index. It illustrates the movements from fiscal 1995, when the last revision of the taxable income threshold was made, to 2024, indexed to 100 with 1995 as the base year. For reference, the trend in total cash compensation (up to 2023) and the national weighted average minimum wage are also shown.

Figure 1: Comparison of Consumer Prices, Cash Compensation, and Minimum Wage

— Indexed to (FY)1995 —

Note: Fiscal years are used for the national weighted average minimum wage and calendar years are used for the consumer price index and total cash compensation.

Note: Fiscal years are used for the national weighted average minimum wage and calendar years are used for the consumer price index and total cash compensation.

Sources: Prepared by the author, after indexing to 100 with 1995 as the base year, from the following sources.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Nationwide Minimum Wages by Region” Consumer Statistics Division, Statistical Survey Department, Statistics Bureau, “2020-Base Consumer Price Index”

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Monthly Labour Survey Special Edition” (November 2024)

Figure 1 illustrates how consumer prices fell almost continuously from 1995 to 2010 before subsequently recovering to a level of 113.1 in 2024. Based on this index, the legitimate increase of the taxable income threshold is 135,000 yen from 1,030,000 yen in 1995 to 1,165,000 yen in 2024. Moreover, since the consumer price index shown here only reflects changes up to 2024, if prices continue to rise, further increases in the taxable income threshold using a new index will be necessary from 2025 onward.

Turning to the other two price indices provided for reference, it should first be noted that the growth rate of total cash compensation is significantly lower than the consumer price index. As a result, it is evident that real wages have continued to decline since 1995. Notwithstanding the possibility that real wages will rise with progressive wage increases in the future, an adjustment to the taxable income threshold based on the growth in total cash compensation since 1995 would necessitate a reduction in the threshold.

On the other hand, the national weighted average minimum wage has increased significantly since 2010, with the index reaching 172.7 in 2024, representing an increase of approximately 73% compared to 1995. Using this index to revise the taxable income threshold would raise it from 1.03 million yen to 1.78 million yen, also aligning with the DPFP’s proposal to raise the threshold.

Regarding this proposal, it should be noted that when prices are rising, adjustments to the taxable income threshold should be based on consumer prices. Moreover, since 1995, the rate of increase in the minimum wage has been significantly higher than the growth of total wages. As a result, this income adjustment is likely to lead to a unilateral increase in the taxable income threshold.

The review of the taxable income threshold is also addressed in the “2025 Tax Reform Outline” (Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito). Based on the rate of increase in consumer prices since 1995 and the fact that the consumer price index for basic expenditure items, which includes many daily necessities, has risen by over 20% from 1995 to 2023, it is proposed to raise the taxable income threshold from 1.03 million yen to 1.23 million yen.

This paper has considered how to address the two income barriers. The root cause of the first barrier is the system of Category III insured persons, which allows dependents to earn up to 1.30 million yen without paying social insurance premiums. This system should be abolished, replaced by a system of tax relief to reduce the burden of social insurance premiums for all workers if their income is below a certain level.

To address the second barrier, it is vital to review the taxable income threshold within the tax system during periods of rising prices. The actual review of the threshold should be conducted based on a neutral consumer price index that reflects taxpayers’ purchasing power. It is crucial to provide the Japanese public with a sound explanation and response regarding measures to address both barriers.

References

Democratic Party For the People (2024) “Increasing Take-home Pay. Moving Japan with ‘Solutions over Confrontation’”

https://new-kokumin.jp/file/DPFP-PolicyCollection2024.pdf

Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito (2024) “2025 Tax Reform Outline”

https://partsa.nikkei.com/parts/ds/pdf/20241220/20241220.pdf

Public Relations Office “Launch of ‘Income Barrier’ Countermeasures! How Will Part-time and Casual Workers Be Affected?”

https://www.gov-online.go.jp/article/202312/entry-5288.html

Eiji Tajika (2023) “‘Income Barriers and Support Packages’ — What Is the Essence of the Problem?” ZEIKEN, November issue, p.11.

Eiji Tajika (2020) “Public Pension Reform — Abolish the National Pension System and Integrate It into Employees’ Pension Insurance,” The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research

https://www.tkfd.or.jp/research/detail.php?id=3312

![[Policy Research] Water Minfra: A New Strategy for Water-Centric Social Infrastructure](/files_thumbnail/research_2023_Oki_PG_Mizuminhura_png_w300px_h180px.png)