Growing Distortions in the Hometown Tax Scheme (3): Cash Flows and Challenges for Urban Municipalities

July 11, 2024

R-2023-121E

Introduction

The first installment in the "Growing Distortions in the Hometown Tax Scheme" series of articles discussed the basic mechanisms of the system and how they have evolved over time, as well as the issues involved, while the second article examined the role of private businesses in the system and the associated problems. This final article will provide an overview of how the funds from hometown tax donations actually flow through the economy. In addition, insights gained from the first Hometown Tax Donation Opinion Exchange Session held at The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research in November 2023 will be introduced and shed light on the real situation facing urban municipal governments. They are grappling with the largest distortion of the system—namely, the outflow of hometown tax donations.

Differences in Cash Flow between Ordinary Taxation and Hometown Tax

With hometown tax donations, donors can receive return gifts worth up to 30% of their donation amount, but in exchange they receive fewer administrative services from their municipality of residence[1]. If they had simply paid their regular residential tax instead of making a donation, they would not receive any return gifts but they would be able to receive certain administrative services from their municipality of residence. So how do the fund flows differ in these two cases?

Individual Residential Tax

Individual residential tax (hereinafter referred to as “resident tax”) is often described as "something that residents and others in a community broadly share the burden of paying (such as membership dues for the local community)"[2]. While public services are provided through a division of responsibilities between the national and local (community) governments, services closely tied to daily life (e.g. education, welfare, fire/emergency services, garbage disposal) are provided by local governments, with resident tax serving as the key source of revenue.

For ease of understanding, let’s consider the example of Kawasaki City in Kanagawa Prefecture. In the explanation above, Kanagawa Prefecture and Kawasaki City correspond to the "local (community)" level, and residents pay resident tax in the form of prefectural resident tax to the prefecture and municipal resident tax to the city. In return, residents receive administrative services from both the prefecture and the city, making the flow of funds extremely simple.

Hometown Tax

Whereas the return for regular tax payments is administrative services, the return for hometown tax donations is tax deductions and return gifts. Unlike administrative services, which target the residents of a given area and do not necessarily directly benefit the individual taxpayer, hometown tax donations provide a direct benefit to the donors themselves in the form of return gifts, which understandably makes such donations generally more appealing to people. However, it should be noted that hometown tax donations may result in the donor being unable to receive future administrative services from their residential municipality.

Compared to the movement of resident tax funds, the hometown tax cash flow is quite complex[3]. Consider the case of a Kawasaki City resident with an annual income of 7 million yen from employment who makes a 30,000 yen hometown tax donation to Miyazaki City in Miyazaki Prefecture. Of that 30,000 yen donation, 2,000 yen is borne by the donor, while 28,000 yen is deducted from their taxes. The breakdown is as follows:

- National tax (income tax) deduction = 6,440 yen

- (Hometown tax amount - 2,000 yen) x "Income tax rate" = 28,000 yen x 0.23

- Local tax (resident tax) deduction = 21,560 yen[4]

- Kanagawa Prefecture deduction = 4,310 yen

- 21,560 yen x 0.2

- Kawasaki City deduction = 17,250 yen

- 21,560 yen x 0.8

- Kanagawa Prefecture deduction = 4,310 yen

When taxes are deducted, this results in a reduction in national and local government tax revenue. In this case, the national government faces a tax revenue reduction of 6,440 yen, the prefectural government 4,310 yen, and the municipal government 17,250 yen.

So, what happens to Miyazaki City as a result of this hometown tax donation from donors in Kawasaki?

- Donation received = 30,000 yen

Kawasaki City, which should have originally received 17,250 yen in resident tax, is unable to record this as revenue, with most of it instead going to Miyazaki City. Looking at the situation for Japan as a whole, however, there is no overall increase or decrease in tax revenue.

Miyazaki City, as a municipality, cannot simply pocket the 30,000 yen donation; it needs to "invest" in preparing return gifts in order to receive the donation. This includes administrative work for processing the hometown tax donation documents, as well as expenses for the return gifts themselves, shipping costs, handling fees, and so on. The strict, new 50% rule introduced in October 2023 stipulates that these expenses must be kept to 50% or less of the donation amount, i.e. the remaining 50% stays with Miyazaki City.

Macroeconomic Flow of Funds of Hometown Tax

In understanding the flow of hometown tax donation funds, two important points can be gleaned from the hypothetical example above. First, hometown tax donations can only be realized through the sharing of burdens among the national government, prefectures, and municipalities. Second, the municipality receiving the donation incurs expenses amounting up to 50% of the donation amount.

A third point that needs to be considered is the movement of the local-allocation-tax-grants from the national government to local governments. For the vast majority of municipalities, 75% of the donations made by their residents is supplemented through local-allocation-tax-grants from the national government to municipalities. Since the original source of hometown tax donations is resident tax, this rule applies to the revenue shortfalls. It is worthwhile to mention that the source of the local-allocation-tax-grants is national taxes, meaning the hometown tax donation system also relies on the national government's burden in this sense. Hometown tax donations have shown annual growth exceeding 20% over the past five years, and as the scale increases, both local-allocation-tax-grants and income tax deductions rise, increasing the national government's burden. However, thanks to this national government's burden, the negative impact on municipal administrative services for residents due to the outflow of hometown tax donations is mitigated.

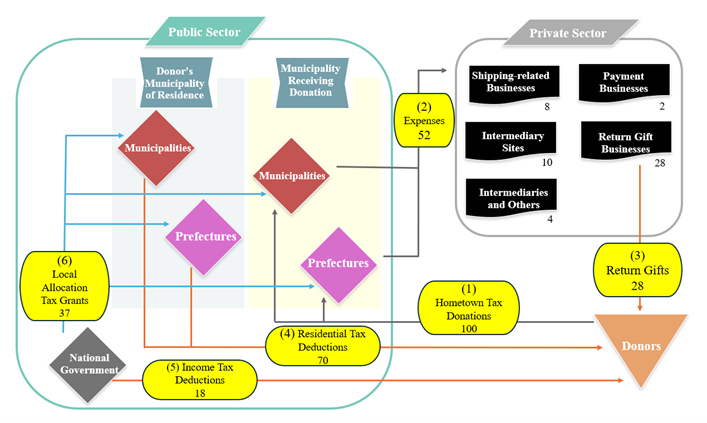

Taking the above three points into account, Fig. 1 illustrates the macro-level flow of funds related to hometown tax donations. Hometown tax donations from donors go to the recipient municipal or prefectural government (Path (1)). The recipient government outsources work to the private businesses listed by paying expenses (Path (2)), and the return gifts are sent to the donors (Path (3)). Meanwhile, donors can receive resident tax deductions from their residential municipalities and income tax deductions from the national government (Paths (4) and (5)). Additionally, the vast majority of municipalities nationwide have 75% of the outflow from their residents' hometown tax donations covered by local-allocation-tax-grants from the national government (Path (6)).

Figure 1 Overview of Hometown Tax Cash Flow (Fiscal Year 2022)

Source: Computed by the author

Note: If we assume the total amount of hometown tax donations, at 965.4 billion yen, to be standardized at 100, the values for each item have been benchmarked (e.g. return gifts amount to 268.7 billion yen, or 268.7÷965.4×100≒28). This includes estimated values. For details on data sources and calculation methods, refer to the appendix at the end of this article. The orange arrows represent the portions corresponding to the returns received by donors for their donations. While return gifts are in the form of actual goods or services rather than money, they are included here to signify the returns on donations. The blue arrows indicate the flow of the local-allocation-tax-grants. The arrows point both toward the donor's residential municipality (A) and the municipality receiving the donation (B) because, except for non-receiving entities, municipalities participating in the hometown tax donation system receive grants. In reality, municipality A also receives hometown tax donations from other donors for the most part, making it difficult to distinguish municipality A from municipality B on a macro level. This distinction is made here, however, to clearly differentiate between cases where hometown tax donations flow in and flow out, as emphasized in the first article of this "Growing Distortions in the Hometown Tax Scheme" series.

Challenges for Urban Municipalities

Incidentally, what kinds of municipalities comprise the "non-majority" that does not receive the 75% supplementation through local-allocation-tax-grants for outflows? These refer to non-receiving entities of the local-allocation-tax-grants, such as Kawasaki City and the 23 wards of Tokyo at the municipal level, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government at the prefectural level, who cannot receive the 75% supplement for outflows. While it can be said that non-receiving entities have relatively sound finances, it is not difficult to imagine the severe situation faced by municipalities such as Kawasaki City, which is experiencing an annual outflow of around 12 billion yen (nearly 8,000 yen per resident) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Impact of Hometown Tax Outflow on Non-Receiving Entities

|

Non-Receiving Entity |

Outflow Per Resident |

|

Minato Ward, Tokyo |

26,535 yen |

|

Shibuya Ward, Tokyo |

19,873 yen |

|

Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo |

11,247 yen |

|

Setagaya Ward, Tokyo |

10,737 yen |

|

Koto Ward, Tokyo |

8,961 yen |

|

Suginami Ward, Tokyo |

8,385 yen |

|

Kawasaki City, Kanagawa |

7,949 yen |

|

Ota Ward, Tokyo |

6,800 yen |

|

Nerima Ward, Tokyo |

5,899 yen |

Note: The figures represent the municipal resident tax deduction per resident for the non-receiving entities of local-allocation-tax-grants (9 entities) among the top 20 entities in terms of municipal resident tax deductions for fiscal 2023 taxation.

Source: Calculated by the author based on the Municipal Tax Policy Division, Local Tax Bureau, Affairs and Communications (2023) "Survey Results on the Current Status of Hometown Tax Donations (for Fiscal 2023 Implementation)" and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2023) "Population, Population Census and the Population Estimates Based on the Basic Resident Registration."

In light of the above situation, The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research invited four urban municipal governments that ranked in the top 20 for hometown tax donation outflows (i.e. municipal resident tax deductions) in fiscal 2023 taxation to participate in the first Hometown Tax Donation Opinion Exchange Session in November 2023.

The main points from the lively discussion that transpired are summarized below:

- Among the four municipalities, there were both recipients and non-recipients of local-allocation-tax-grants. Particularly for non-recipients, residents' hometown tax donations represent a complete outflow externally, posing a fiscal burden. With the scale of hometown tax donations steadily expanding, there is a strong sense of crisis that This trend will be even stronger in the future.

- The one-stop exception system that simplified hometown tax donation procedures had the effect of broadening the user base. Here, the national income tax deduction portion is replaced by the municipal resident tax deduction, increasing the burden on municipalities, who are opposed to it. The contribution to increasing outflows due to the expanding user base is also a matter of concern.

- As it becomes increasingly difficult to put a stop to outflows, more municipalities are actively trying to promote inflows through measures such as enhancing return gifts; some, however, choose not to participate in the return gift competition.

- Details such as the breakdown of expenses of private companies including the companies operating intermediary websites are not disclosed, making it difficult to judge whether the expenses are appropriate. This is a vexing issue given that the introduction of the new 50% rule imposes stricter regulations on expenses.

I plan to continue elucidating the issues surrounding the impact of hometown tax donations on municipalities through collaboration with these parties as part of The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research's program activities in fiscal 2024 and beyond.

(The author wishes to express his gratitude for the valuable comments received from Wakako Takaoka of the NLI Research Institute and Takashi Oshima of Kawasaki City in preparing this article.)

Appendix: Methodology for Calculating Figure 1 Hometown Tax Cash Flow (Fiscal Year 2022)

This figure was created based on Wakako Takaoka's "Flow of Funds in Hometown Tax—Where is the Room for Reconsideration?" (NLI Research Institute, NLI Research Report, August 15, 2022); I also incorporated my own calculation methods upon consideration of additional details on calculation methods provided by Ms. Takaoka. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Ms. Takaoka.

Data for the following items were obtained from the Municipal Tax Policy Division, Local Tax Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2023) "Survey Results on the Current Status of Hometown Tax Donations (for Fiscal 2023 Implementation)"l: (1) Hometown tax (965.4 billion yen, p. 2); (3) Return gifts (268.7 billion yen, p. 6); (4) Resident tax deductions (679.7 billion yen, p. 9); and (2) Expenses (496.9 billion yen). The final figure was obtained by multiplying 451.731 billion yen (p. 6) by 1.1 to adjust for the under-reporting of expenses in Fig. 1 of my previous article, "Growing Distortions in the Hometown Tax Scheme (2): The Pros and Cons of Private Sector Involvement," The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research Review, R-2023-104E.

For (6) local-allocation-tax-grants (352.8 billion yen), I obtained the deduction amounts for each municipality from the Municipal Tax Policy Division, Local Tax Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2023) "Results of Residential Tax Deductions for Fiscal 2023 Taxation," excluded non-receiving entities, including the 23 wards of Tokyo, totaled the deduction amounts (municipal resident tax deductions + prefectural resident tax deductions), and multiplied by 75%.

I calculated (5) Income tax deductions (174.2 billion yen) as follows: according to the aforementioned Survey Results, there were 4.649 million users of the one-stop exception system for hometown tax donations and 4.262 million users filing tax returns. The donation amounts are: for one-stop, 2,000 yen x 4.649 million + resident tax deductions for 4.649 million people (Equation 1); for tax returns, 2,000 yen x 4.262 million + resident tax deductions for 4.262 million people + income tax deductions for 4.262 million people (Equation 2). Here, the sum of the left hand sides of both equations = total donations from all people (4.649 million + 4.262 million) = one-stop donation amount + tax return donation amount = 965.41 billion yen. The sum of the first terms on the right hand sides of both equations = all people (4.649 million + 4.262 million) x 2,000 yen = 17.82 billion yen. The sum of the second terms on the right hand sides of both equations = resident tax deductions for all people = the aforementioned (4) = 679.67 billion yen. Therefore, calculating the income tax deduction portion as the residual based on the above, the income tax deductions for 4.262 million people = 965.41 billion yen - (17.82 billion yen + 679.67 billion yen) = 267.98 billion yen.

Calculating the previous year's figure using the same method yields 248.2 billion yen, which differs significantly from Ms. Takaoka's estimate of 161.3 billion yen. This is because Ms. Takaoka made a careful estimate that considered factors such as the timing differences between the fiscal year-based donation receipt figures and year-based deduction figures, as well as the existence of well-intentioned donors. Here, I arrived at an estimate of 174.2 billion yen by assuming that the ratio of Ms. Takaoka's estimate to the residual calculated value remains the same as that of the most recent year.

For (6) Private sector expenses, I used the costs for procuring return gifts (268.728 billion yen), costs for sending return gifts (73.179 billion yen), and settlement-related costs (19.721 billion yen) from p. 6 of the Survey Results as the respective expenses for return gift businesses, shipping-related businesses, and payment businesses. For intermediary sites, I assumed 10% of the 965.4 billion yen in hometown tax donations. Intermediaries and others is the amount obtained by subtracting these expenses from the total (2) expenses, including personnel costs for municipal staff involved in hometown tax donations, as well as the expenses of private businesses other than intermediaries and intermediary sites.

[1] In reality, many municipalities ensure the quality and quantity of services they provide via measures such as drawing down their reserves. However, in the long run, the services municipalities can provide will decrease in response to the decrease in tax revenue.

[2] The explanation in this paragraph follows the explanation provided by the Ministry of Finance.

[3] The following discussion excludes special cases such as the special income tax rate for reconstruction, hometown tax donations without return gifts, and hometown tax donations to the donor's municipality of residence (with no return gifts).

[4] For resident tax, the income-based tax rate for the income-based portion that seeks a burden commensurate with income is prefectural resident tax (4%) + municipal resident tax (6%) = 10% of income. However, for Kawasaki City, which is a government-designated city, it is prefectural resident tax (2%) + municipal resident tax (8%).

![[Policy Research] Water Minfra: A New Strategy for Water-Centric Social Infrastructure](/files_thumbnail/research_2023_Oki_PG_Mizuminhura_png_w300px_h180px.png)